A closer look at an eelgrass inhabitant – the Dungeness crab

by Jason Toy (Undergraduate student in the UCD ZEN class)

Several weeks ago, I was out at Bodega Bay with my classmates from the UCD ZEN course collecting field data for our research projects. As I stood out there in the water in my borrowed waders, I observed quite a few different species of invertebrates as they made their way through the bed of eelgrass. Most were quite familiar to me at that point, but there were a few species, including the Dungeness crab, Cancer magister, that I had not thought of as typical eelgrass inhabitants. I decided to do a little research on the life history of these crustaceans in order to better understand the importance of estuarine seagrass beds to this – and potentially other – important crustacean species.

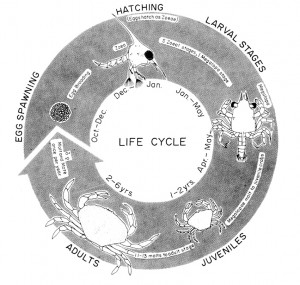

I was surprised to learn that these crabs move around quite a bit during their life histories. Adults mate in nearshore coastal locations in the Pacific Northwest throughout the spring (Pauley et al., 1989), a process in which the male embraces the female for up to 7 days before she molts, after which the actual transfer of sperm occurs. She stores this sperm for about a month until she extrudes her eggs and, in the process of doing so, they are fertilized (Tasto et al., 1893). But her care doesn’t end there. She protects her eggs by storing them on her abdomen for several months until winter (typically December – January). Then one day, these 1-2 million eggs hatch and the baby crabs leave their mother and enter a 105-125 day planktonic larval period. During this time the young Dungeness crab goes through many developmental changes, moving through 5 zoeal and 1 megalopal stages. After reaching the megalopa stage, the young crabs settle out onto the bottoms of bays and estuaries, where they molt into their first juvenile crab stage and begin to actually resemble real crabs.

During field sampling, Jason and classmates found a few juvenile Dungeness crabs hiding amid the eelgrass in Bodega Bay, California

This is where seagrass comes in! Coastal estuaries (like Bodega Harbor) play a critical role for juvenile Dungeness crabs as a nursery. Large numbers of juvenile crabs benefit from the protection and substrate provided by beds of eelgrass (Zostera marina). They cling to and hide within the grass, consuming other small organisms within the habitat (amphipods, isopods, polychaetes, essentially whatever they can catch!) (Pauley et al., 1989). After several molts, subadults and adult Dungeness crabs begin to leave the eelgrass beds and move offshore, but a few do remain in inland coastal waters, hiding among the eelgrass blades.

The role of seagrass beds in the life history of Dungeness crabs is an important interaction to talk about because it is an example of an economic benefit (known as an ecosystem service) provided by seagrass beds. Seagrasses are critical species in coastal environments around the globe, as they form habitat structure and promote a large diversity of organisms. However, like the coral reefs, they are currently in decline due to the effects of human activities. The connection of an economically important species such as Cancer magister to these seagrass ecosystems, however, can help bring attention to this issue, and provide an incentive for the preservation and restoration of this habitat. Help spread the word!

For more information, check out these references:

Pauley, G. B., Armstrong, D. A., Citter, R. V., & Thomas, G. L. (1989). Species Profiles: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Pacific Southwest): Dungeness Crab. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services Biological Report 82(11.121): 7-8.

Tasto, R. N., & Wild, P. W. (1983) Life History, Environment, and Mariculture Studies of the Dungeness Crab, Cancer Magister, With Emphasis on The Central California Fishery Resource. California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 172, 319-320. Retrieved June 11, 2014, from http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt1k4001gs&&doc.view=entire_text

Jason is an aspiring marine ecologist with a passion for all things science. He is a rising senior at UC Davis studying evolution and ecology. His dream job is to be a research SCUBA diver. This summer he will be working in Dr. Jay Stachowicz’s marine ecology lab at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Science boot-camp at the Bodega Marine Lab

by Julie Blaze (UC Davis undergraduate, ZENtern)

Marine biologists don’t often find themselves trekking through dense remote jungles or climbing desolate mountains to conduct their research. Some would say we’ve got it pretty easy – the ocean covers around 70% of the earth’s surface, and studying biodiversity can be as easy as walking out to the coast and digging in the sand. The only downside to the job is that we are captives to the ebb and flow of the tides. My classmates and I in the ZEN class at UCD found that out the hard way when we took a field trip to the Bodega Marine Laboratory to survey the eelgrass growing in Bodega Harbor.

As someone who enjoys sleep, I can honestly say it is difficult to wake up at 5:30 am for any reason. Awake before the sun and trudging across the mud flats before its first rays had even reached the water, I know I wasn’t the only one thinking of the warm, comfy beds we had left behind. My boots were a little too big and kept getting stuck in the mud – I almost went sprawling face down into the mud more than once. As the sun rose, I wondered what we must have looked like to anyone watching from the shore – a zombie-like group of college students floundering in the mud. Slowly we gained more energy and set about surveying a large expanse of the seagrass bed collecting samples and taking measurements. We worked efficiently and conversation picked up as excitement and adrenaline grew with each new discovery and lapping reminder of the incoming tide. At first glance the mudflats and seagrass meadows look barren, but we quickly found that they teemed with life. Critters clung to the grass or buried themselves in the mud – making this eelgrass bed, similar to other seagrass meadows, one of the most diverse ecosystems in the ocean.

After a few hours the water had crept too high for us to work and we headed back to the lab to begin processing our samples. We put in a long day, getting as much done as we could before calling it quits. We all found those cozy beds soon after a late dinner, with the promise of another early field day tomorrow.

The next morning we again rose before the sun and stumbled out into the mud. But this time we were more familiar with the science – the methodology and how to work as a team – and we finished before the water chased us out.

By the end of the weekend I was thoroughly exhausted, but I didn’t care. We had spent an incredible weekend having an amazing adventure. Not only did I learn about the animals and ecosystem we were exploring, but I also learned several things about myself that weekend. First, I learned that I am willing and able to wake up before the sun to do research. Second, not even the wilds of a remote jungle can tempt me away from the mysteries of the ocean. And, finally, one lesson I will never forget – it’s easy to stay awake once your boots flood with freezing cold seawater. But, it’s even easier when you’re also out exploring a location as interesting as a Bodega Bay seagrass bed!

Julie is a graduating senior at UC Davis majoring in Biology. This summer she will be a ZENtern working with Dr. Nessa O’Connor in Ireland. Julie is a true team player and earned the nickname “den mother” during the 3-day, marathon class field trip and subsequent weeks of sample processing back on campus.

Photos contributed by Aaron Goodman.