Global ecological challenges require large-scale scientific networks

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN postdoc and coordinator)

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN postdoc and coordinator)

While at Ecological Society of America meeting (#ESA100) in Baltimore in August, 2015 I attended and participated in the discussions surrounding a special session titled “Collaborative Ecological Research Networks: Sociology, Successes, and Future Opportunities.” I wrote a blog post about this session and the lessons we’ve learned from running ecological research networks like ZEN. This post originally appeared on the PLOS BLOGS website on August 31, 2015 and can be accessed here. The text is included, below, with additional photos. At the end see an infographic I created on “11 tips for a successful research network.”

“It was a big year,” observed Emmett Duffy, director of the Smithsonian Institution’s MarineGEO program, at the 100th Ecological Society of America (ESA) meeting in Baltimore, MD in reference to the society’s establishment in 1915. “World War I was raging, the Lusitania went down, Congress denied women the vote, and John Muir had just died.”

But, Duffy went on to say, in those dark times Muir had lit a spark and the appreciation of wilderness was growing. It was in this year that the Ecological Society of America was born and began its mission to promote and raise public awareness of ecological science.

But, Duffy went on to say, in those dark times Muir had lit a spark and the appreciation of wilderness was growing. It was in this year that the Ecological Society of America was born and began its mission to promote and raise public awareness of ecological science.

In the century since we’ve vastly improved our understanding of the natural world while simultaneously radically transforming vast swaths of the Earth’s surface.

It struck a chord when Duffy asserted that the once predominantly curiosity-driven and inquiry-based pursuit of ecology to understand nature for its inherent wonder has become eclipsed by today’s model of ecology as emergency medicine based on a need to triage and solve the Earth’s environmental problems.

Scientists are being called upon to tackle increasingly complex issues, which has broadened ecology and driven the need for greater interdisciplinary interactions among us. With global issues such as climate and biodiversity change threatening local ecosystems, large-scale approaches to ecological science have rapidly risen within the field.

A particularly exciting development is the growth of grassroots networks using comparative experimental and observational approaches, which feature simultaneous and unified data collection across multiple locations.

Such research networks allow scientists to directly address large-scale issues by capitalizing on naturally occurring environmental and biological gradients. They work similarly to clinical trials conducted at multiple hospitals to test drug efficacy across diverse demographics – just as a drug might operate differently in younger and older populations so might a given ecological process operate differently at lower and higher latitudes, etc.

Yes, but how?

How can we best organize and sustain these networks given the inherent challenges of managing diverse teams distributed across large spatial distances under shrinking and uncertain funding climates?

Almost four hours of talks, discussion and synthesis by over 50 ecologists at a special session during ESA titled “Collaborative Ecological Research Networks: Sociology, Successes, and Future Opportunities” provided some answers. It also produced more questions about how to leverage such networks to best conduct the next 100 years of ecological research. Here are some highlights from that still emerging dialogue.

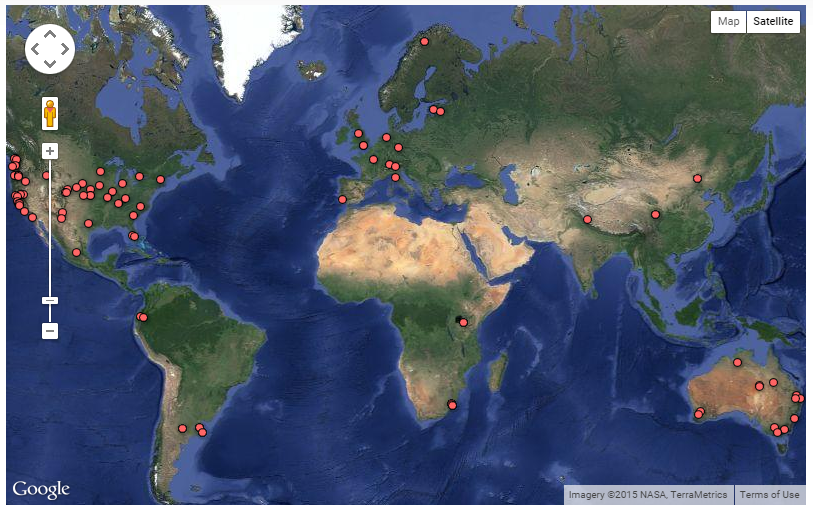

Research networks use identical protocols across broad spatial scales (Nutrient Network Global Research Cooperative)

Eric Seabloom, professor at Univ. Minnesota, opened the session and highlighted several tools scientists have for understanding ecological processes. Traditional single experiments, such as those conducted by a single investigator working in one or a few locations, can provide rigorous tests of specific ecological theory but can rarely be applied directly to other regions. Reviews and meta-analyses of these experiments begin to overcome such context-dependency to uncover overarching ecological patterns, but these approaches lose the benefit of direct comparability as cross-study variation in methodology often emerge as a confounding, or at the very least co-varying, factor.

Observational networks, often in the form of sensor arrays, provide real-time data collected in comparable units. But experimental networks push the envelope of ecological research even further, combining the benefits of the other three approaches with consistent methodology. They provide the opportunity to rigorously, directly test whether our models of nature have global generality and how they are affected by local context. It is thus not surprising that new ecological research networks are emerging rapidly in ecosystems ranging from grasslands and lakes to seagrasses and kelp forests.

Several existing ecological research networks participated in this special ESA conference session.

Students and volunteers work with scientists to survey different plant populations for the Global Garlic Mustard Field Survey project (Robert Colautti)

Eric Seabloom spoke regarding the Nutrient Network which studies over 40 grasslands worldwide, Emmett Duffy on the Zostera Experimental Network(ZEN) conducting experiments in 50 underwater seagrass beds across the Northern Hemisphere, and Kathleen Weathers from the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) which monitors lakes in over 51 countries. Also contributing to the conversation were Ruth Hufbauer from the Global Garlic Mustard Field Surveys featuring academics and citizen scientists tracking approximately 360 globally distributed populations of garlic plants, and Claus Beier from the more loosely aggregated Climate Change Manipulation Experiments in Terrestrial Ecosystems (ClimMani) network.

Despite the tremendous advantages of ecological research networks, the speakers all highlighted significant challenges, especially those inherent to conducting data-intensive research across large spatial scales. Networked ecology comes with a cost – in both infrastructure for project management and data curation.

Additionally, even with numerous broadly distributed sites, there will be data gaps as not all possible locations can feasibly be included. Sites within the network will have some degree of spatial autocorrelation and climate heterogeneity. Incorporating partners from targeted regions encompassing specific environmental regimes can help, but it doesn’t resolve the people and cultural-issues that can arise from such broadly distributed endeavors.

It’s all about the people

Ecological networks rely first and foremost on the people involved – their passion, engagement and commitment to the science – to succeed. The take home message from recent papers on what makes a productive science team is surprisingly simple: 1) members must truly care about the science, and 2) they have to trust each other (Borer et al. 2013; Hampton & Parker 2011).

Network partners have to be willing to invest considerable effort in both time and money, and do so under uncertain terms of any tangible ‘payback’ for their participation. They need to trust that their shared data will be used appropriately and their efforts rewarded. Charismatic, respected and transparent network leadership can help, as can having strong track records of publications and funding. Meeting face to face and repeated informal interactions on neutral ground are critical for helping partners care about, and trust, one another. Clear ground rules and expectations for participation (from data collection, sharing and analysis to publication) must be explicitly established from the beginning. Network leaders must provide effective data management and accessibility and the opportunity for all partners – from professors to graduate students and postdocs – to engage fully in the process. Just as the data itself have needs – to be collected rigorously and according to specific protocols – the people in the network also have needs and supporting both young and senior investigators is critical for network growth and persistence.

Research networks can produce greater quality and quantity of products

Despite the challenges of conducting networked research, the speakers highlighted the important benefits of large-scale collaborations which extend beyond the scope of any specific experiment.

“Network papers and reports are often so well vetted within the network prior to submission to a journal that their quality is very high,” Eric Seabloom noted.

The large community of scientists also helps spur novel research avenues.

“If a network partner comes up with a great idea it’s likely to be adopted and conducted across many sites,” said Elizabeth Borer, professor at Univ. Minnesota and co-founder of NutNet. Eric Lind, a NutNet postdoc, drove this point home with a presentation derived from network data exploring the role of phylogenetic relatedness on grassland biodiversity-functioning dynamics – something the network never set out to test initially but emerged from the years of coordinated data collection.

And, if publications are a measure of network success then GLEON, the largest and oldest of the networks represented at the session, certainly can be proud of Kathleen Weathers’ tally of 143 network publications spanning 356 authors.

A broad distribution can improve research products, but also poses significant challenges (Nutrient Network field sites, 2015)

Measuring success

While measuring success is critical for network accountability, simply counting the number of publications, citations, or grants doesn’t quite capture the productivity and diversity of positive interactions fostered by those approaches.

Persistence and expansion can be useful metrics, but “growth on its own is not sufficient proof of network success,” said Richard Inouye, Associate Dean at Utah State Univ., as he spoke during the special session about “Networking into the Future.”

Research networks without sufficient age structures, incorporating both young and senior scientists, are unlikely to persist. The best networks should incorporate ongoing opportunities to engage and rekindle existing members across multiple career stages. But, Inouye cautioned, network dissolution isn’t a necessarily a measure of failure either.

“There are many reasons why successful networks may dissolve,” he said. Perhaps the network met its initial goals, solved its main questions. Perhaps the community it created is so well integrated and self-sufficient that top-down oversight is no longer necessary or useful.

Network persistence requires funding, sufficient age structure, and strategies for data management (GLEON, Grace Hong)

How to provide recognition for the work done?

But, with so many people engaging in a given ecological research network, how can we provide individual participant recognition or measure individual successes?

Authorship on publications is a start, but with large numbers of co-authors the contributions of a given individual can become rapidly diluted. Publishing participation appendices with detailed co-author roles can provide clarification, assuming search and promotion committees take the time to download and read them. Developing network websites with pages highlighting students and other network members who have yet to participate at the level of a co-author can also provide recognition, foster connections among network members, and meet grant reporting purposes.

A personal perspective

Pamela Reynolds and members of the Zostera Experimental Network sample seagrass biodiversity (Chris Nicolini)

But what continues to amaze me is how strongly participants feel about their networks. Kathleen Weathers was almost nostalgic as she described the strong sense of community fostered by GLEON, who’s first generation of students are now professors running their own labs and continuing to engage in their global lake science.As a postdoctoral researcher and coordinator for the marine ecological research network ZEN, I’ve experienced firsthand the incredible power these networks have in tackling some of Earth’s most challenging environmental issues.

Elizabeth Borer agreed, acknowledging that despite the intense commitment necessary to running a network she still feels, most days, that she gets more out of her involvement with NutNet than she puts in. This is also generally true for the agencies funding such research networks.

“It costs only $4K to setup one of our grassland sites – a site we can typically continue to study for decades,” said Borer.

Our marine network was launched with a single standard NSF research grant,” Emmett Duffy acknowledged, “but the in-kind investment and participation of our partners and their home institutions stretched it to cover 50 seagrass beds worldwide. NSF is getting a tremendous return on this modest investment in a research network.”

As an early career researcher I agree with my network mentors, although inevitably there are days when the coordination and data curation activities are all-encompassing. It is in those moments that the people remind me why I’m in it for the long haul. One day I’m speaking with a researcher in Portugal or Japan, the next North Carolina or San Diego, and their excitement for our science is contagious. In listening to their local, site-based anecdotes I always learn something new – I begin to connect dots I didn’t even know existed, develop perspectives to better understand ecological theory and link our science with important policy. I read an email from a student and realize that their experience working with our network has changed how they think about the world and helped launch their science career.

Participating in an ecological research network is rewarding but requires significant dedication (Zostera Experimental Network, Chris Nicolini)

But engaging most deeply with a research network isn’t for everyone. Organizing, motivating and maintaining coordinated research activities (as well as continually searching for funding for meetings, infrastructure and supplies) takes considerable effort. Research networks certainly benefit from the time and energy of junior scientists, but given the longer-term nature of the data collection and slowly accumulating results – which are often at odds with the publish or perish academic culture – some caution is necessary.It’s these types of engagements that keep those of us in research networks coming back for more and motivate us to encourage participation in this open style of science. When networks are done right, junior scientists can expand their networking opportunities and research programs, and established scientists can in turn learn new up-and coming skills.

One strategy is to wait to invest heavily in a network only toward the end of your career or once you are well established in the field. But many of the speakers and participants at the ESA special session presented compelling counter-evidence for that assessment. Like a healthy stock portfolio, scientists at all career stages should engage in a diversity of projects.

For both the sake of advancing science and career, one of those investments we should all make in the next 100 years of ecology is participating in a research network. Collaboration produces rich and diverse rewards for both the investigators and the field at large. Hopefully the next generation of ecologists, and funding agencies, will agree.

Further Reading:

Borer, E.T, Harpole, W.S., Adler, P.B., Lind, E.M., Orrock, J.L., Seabloom, E.W., and M.D. Smith. 2014. Finding generality in ecology: a model for globally distributed experiments. Ecology and Evolution, 5, 65–73. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12125.

Hampton, S.E., and J.N. Parker. 2011. Collaboration and Productivity in Scientific Synthesis. BioScience, 61(11):900-910. 2011. doi:10.1525/bio.2011.61.11.9.

Pamela Reynolds is a postdoctoral researcher at UC Davis and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Her research explores the causes and consequences of marine biodiversity in a changing world. Her postdoctoral research focuses on seagrass ecology, predator-prey interactions, and salt marsh restoration. Pamela coordinates and manages the Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN), a large international team of marine ecologists. More about her research be found at the ZEN website. Twitter @PLNReynolds.

ZEN at #ESA100

In August 2015 several of the ZEN partners traveled to Baltimore, Maryland to present their research and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Ecological Society of America (#ESA100).

In August 2015 several of the ZEN partners traveled to Baltimore, Maryland to present their research and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Ecological Society of America (#ESA100).

This was a very large meeting and a big occasion for the organization - even the president wished ESA a happy birthday!

“Happy 100th birthday to the Ecological Society of America… I want you to know that I’m grateful that ESA has been by our side, helping us bring science to the table to address climate change, preserve our oceans, and combat droughts and wildfires. Your mission and message couldn’t be more urgent. Today like one hundred years ago, you remind us that the health of our nation depends on the health of our environment and I know that you will be at the forefront of this national mission for your next hundred years. So thank you, and congratulations.” – President Barak Obama (Transcript provided by ESA.)

During the meeting, ZEN partner Randall Hughes discussed the use of common garden experiments to test responses of marine populations to temperature change, and her postdoc Torrie Hanley showed legacy effects of eelgrass genotypic diversity on productivity. Mary O’Connor synthesized trends in marine biodiversity losses (and gains), and Joel Fodrie demonstrated the role of landscape context on oyster reef ecosystem services. ZENtern Kendra Chan presented a poster on her undergraduate honors thesis project on the role of eelgrass genotypic diversity and grazer richness on eelgrass decomposition. Pamela Reynolds discussed emerging results from recent ZEN research activities, and Emmett Duffy explained the promise of networks like ZEN for tackling large-scale ecological questions. Pamela live-tweeted while at the meeting - check out her feed @PLNReynolds.

Typically when we attend conferences there is very little time to explore the surrounding city. Most of our time is spent sitting in conference rooms listening to talks, discussing ideas with colleagues in the hallway or over lunch, or hiding in a deserted corner to make some final edits to a presentation.

After the close of the ESA meeting several ZEN participants made a special trip to visit the nearby National Aquarium before traveling home. Here are a few highlights from that visit.

The marine ecologists had fun signing Aquarium pledges for each other to become “shore heroes” and further help the ocean.

A book in the aquarium’s store brought the week full circle. Before ESA the convention center hosted BronyCon, a convention for My Little Pony enthusiasts.