ZEN at #ESA100

In August 2015 several of the ZEN partners traveled to Baltimore, Maryland to present their research and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Ecological Society of America (#ESA100).

In August 2015 several of the ZEN partners traveled to Baltimore, Maryland to present their research and celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Ecological Society of America (#ESA100).

This was a very large meeting and a big occasion for the organization - even the president wished ESA a happy birthday!

“Happy 100th birthday to the Ecological Society of America… I want you to know that I’m grateful that ESA has been by our side, helping us bring science to the table to address climate change, preserve our oceans, and combat droughts and wildfires. Your mission and message couldn’t be more urgent. Today like one hundred years ago, you remind us that the health of our nation depends on the health of our environment and I know that you will be at the forefront of this national mission for your next hundred years. So thank you, and congratulations.” – President Barak Obama (Transcript provided by ESA.)

During the meeting, ZEN partner Randall Hughes discussed the use of common garden experiments to test responses of marine populations to temperature change, and her postdoc Torrie Hanley showed legacy effects of eelgrass genotypic diversity on productivity. Mary O’Connor synthesized trends in marine biodiversity losses (and gains), and Joel Fodrie demonstrated the role of landscape context on oyster reef ecosystem services. ZENtern Kendra Chan presented a poster on her undergraduate honors thesis project on the role of eelgrass genotypic diversity and grazer richness on eelgrass decomposition. Pamela Reynolds discussed emerging results from recent ZEN research activities, and Emmett Duffy explained the promise of networks like ZEN for tackling large-scale ecological questions. Pamela live-tweeted while at the meeting - check out her feed @PLNReynolds.

Typically when we attend conferences there is very little time to explore the surrounding city. Most of our time is spent sitting in conference rooms listening to talks, discussing ideas with colleagues in the hallway or over lunch, or hiding in a deserted corner to make some final edits to a presentation.

After the close of the ESA meeting several ZEN participants made a special trip to visit the nearby National Aquarium before traveling home. Here are a few highlights from that visit.

The marine ecologists had fun signing Aquarium pledges for each other to become “shore heroes” and further help the ocean.

A book in the aquarium’s store brought the week full circle. Before ESA the convention center hosted BronyCon, a convention for My Little Pony enthusiasts.

A little closer to home – ZEN in Long Island Sound

by Ally Farnan (College of William and Mary undergraduate, ZENtern)

Even though Long Island is not a conventionally exotic location for a girl from New Jersey to spend the summer, it is starting out to be quite an adventure.

I arrived on site less than two weeks ago and I already feel like a part of the family here in the Peterson lab. I have spent the past week prepping for the ZEN experiments in the lab. Though a crucial step in the process of running experiments and conducting research, spending a week making aluminum packets, labeling, and weighing tins is not exactly thrilling. It is, however, a necessary part of the process, and is giving me some great practice for the eventual post-processing, sorting, and identification of field samples yet to come. I’m still figuring out where everything in the lab is located, but am getting some excellent help from the other undergraduate volunteers working the lab.

Luckily, I get to start running the actual experiments on Monday, which will also be the first time that I get to see the seagrass bed that we will be working in. Since I have been so busy in the lab, I haven’t had the opportunity to get into my wetsuit and see the site. The area that we are located in is beautiful, so I expect that the study site will also be wonderful!

I’m living a short drive from the lab with two graduate students, which gives me an interesting perspective on how different science research is from the typical 9-5 business job. My housemates, Rebecca and Sam, are excellent hosts and it’s so much fun to hear about the different kinds of research that they do. It should be really exciting to delve further into the experimental stages of ZEN so I can gain some hands-on experience myself.

The lab here is nearby, just off the water. The weather has been great most days, so I’ve been able to explore the area by jogging around town and by the beach. I hope to see some more of the sights around where I am staying. All of my new friends in the lab have given me some great ideas for how to spend my free time during the upcoming weekends - I can’t wait to discover what makes Long Island so special.

It is surprisingly chilly here, so I haven’t been brave enough to go swimming just yet since my toes freeze every time I stick them in the water. But, the sun is constantly shining, making for some beautiful drives around town with my windows down. I can’t wait to continue my adventures here by getting some fieldwork experience. I’ve already packed up my wetsuit so I don’t freeze in the cold water!

I’m so lucky to have a bunch of help in the lab, not only to settle me into a new space and help me to learn more about seagrass ecosystems, but also to advise me on some cold weather gear for our fieldwork in the next few weeks! I’m sure my future blog posts will be filled with some exciting fieldwork stories and hopefully I’ll still have a little free time to explore the area and tell you more about those experiences as well!

“Bok” from Croatia!

by Austin Ruhf (College of William and Mary undergraduate, ZENtern)

Bok, or hello, from Croatia! I’m one of the ZENterns from the College of William and Mary and am spending my summer with classmate Dave Godschalk assisting with the ZEN research in beautiful Zadar, Croatia. I have only been at my host site for a week, but so far Croatia has been a welcoming and easy going paradise. Despite a comical amount of initial bureaucracy (it seemed like we needed the equivalent of a social security registration to gain internet access), the locals have been more than accommodating towards my ignorant American self. My host supervisor at the University of Zadar, Dr. Claudia Kruschel, has been fantastic to work with. She seems to never grow tired and goes out of her way to make sure that all of our work is a group effort. She even lent me her daughter’s guitar so I wouldn’t get musical withdrawal during my stay abroad!

The only downside is that the ZEN field sites are subtidal and are so deep that they have to be surveyed by professional divers. This means that the bulk of my and Dave’s work is done in the lab. The facilities are setup differently from the lab back at VIMS, but the work itself is similar. After a strenuous first week, we have settled into a manageable schedule.

Outside of the lab, fellow intern Dave and I have begun to explore Zadar in our spare time. Dave is already hooked on espresso and sparkling water, and I’m trying to discover more about the culture of the young people here. This led me to watch a heavy metal music show in an old puppet theater, which was pretty strange but somehow felt completely natural. We next hope to visit a few of the world-famous beaches here in Croatia, and learn how to best avoid the crowds of German tourists. Who knew that this was such a popular spot for science, and for a holiday?

A buoyant day in the field

by Whitney Dailey (San Diego State University undergraduate, ZENtern)

One of my favorite parts of the ZEN seagrass ecosystem ecology course at San Diego State University this past spring semester was working in the field and learning about seagrass ecology through a hands on approach.

One field day that I will never forget was when we were collecting our predation intensity experiment. The experiment consists of deploying several “tethers”, which are made by gluing grazers (in this case small grass shrimp or snails) to fishing line placed out in the seagrass bed. We then come back later to record whether the animals have been eaten. The purpose of the experiment is to understand the level of predation in the environment and the relatively susceptibility of different types of grazers.

Whitney and classmates at SDSU learn the importance of being prepared for the unexpected – and in bringing weight belts out into the field

However, one of the main lessons that we learned during our time in the field with the ZEN class is that every experiment has its own challenges and the trick is to problem solve and find a way around it. On this particular field day we met the challenge of trying to schedule fieldwork around both our class schedule and the tide. For us this meant struggling to find the tethers in around 3 to 4 feet (1-1.5 meters) of water. While this may not sound challenging, we found it to be very difficult. We would try to dive down, but the extra buoyancy from our wetsuits at that shallow depth made us pop up to the surface right away. So, we just floated on the surface and would reach down and try to find them and pull them out. The trick was not giving up, and remembering to bring a weight belt in the future.

After many failed attempts of trying to retrieve the tethers, we were finally able to hold onto the pieces of rebar we’d installed to mark our experimental plots, and feel around until we found the tether and pulled it out. Every time we found a tether we would get so excited – until we moved on to retrieve the next one. But, with a lot of commitment and perseverance we completed our field day at our ZEN site in San Diego Bay and learned new methods for problem solving during fieldwork. We also learned that in marine ecology (and likely the other sciences) the truly exciting part comes from overcoming challenges, even the ones you didn’t anticipate!

Whitney graduated summa cum laude this May from San Diego State University, receiving her Bachelors of Science in Biology and Environmental Science. She has been working in seagrass ecology as part of Dr. Kevin Hovel’s lab for the past four years including on the initial ZEN projects in 2011-2012. Hailing from Washington, Whitney enjoys playing basketball and taking photographs in her spare time. This fall she plans to being a job as a research technician before applying to graduate school. Whitney will be traveling to work with Dr. Per-Olav Moksnes and his research group in Sweden as par of her ZENternship this summer.

Loving science for the challenge

by Christopher Bayne (San Diego State University undergraduate, ZENtern)

Field days have to be one of my favorite parts of science for two main reasons. The first reason is fairly obvious – we get to go out to the field site, which means getting some exercise, being in the sun, and working in the natural environment. You can’t beat that! The second reason is less intuitive. I really enjoy the challenges of fieldwork and problem solving. No matter how well protocols are planned and how many times you go over them, it seems that the smallest thing can turn into the biggest pain. Even though these problems can be time consuming and counterproductive, they keep you on your toes.

Along those lines, the ZEN predation intensity experiment comes to mind. The first time we deployed the experiment, which tested different materials as potential standardized prey to be used in experiments conducted by all of the ZEN partners, we used braided line threaded through different bait types. We separated each bait into separate bags for “quick and easy” deployment in the field. However, when we reached our field site we soon discovered that, when braided line goes into a bag, the mixture of moving around, getting wet, and Murphy’s law results in a knot so bad that you can barely distinguish one line from another. It just so happens that this occurred to six of our eight different bait types. What do we do?

We approached the problem like you do with so many other unexpected field issues. You accept it and just jump in headfirst. You approach the knot and honestly, there is no apparent advantage of coming at it at any certain way. You just begin trying to separate each line one at a time. You try different things: weaving the bait end through, loosening the most knotted sections, pulling the line through slowly. You swear you’ve undone hundreds of knots yet the ball of tangled string never looks as if any progress was made. Finally, you notice one looks as if it is almost loose. You put all your effort into that and get it out with this silent victory to yourself. Eventually they are all loose and you re-wrap them in a way that they will not get tangled up again. You think about what you could or should have done to avoid this mess. You finish up what needs to be done, knowing you are ready for whatever comes next.

In the end, the problem of the knotted line may be small but it is symbolic of the problems researchers face all the time. Little complications creep out of nowhere, completely unexpected. You try a million different solutions and begin to loose faith when nothing seems to work. If you have enough patience, the knot will eventually loosen and you will be victorious, swearing that you will never make that mistake again. This is why I have chosen to do science. It is challenging in so many ways. Learning the correct terminology, setting up experiments, finding solutions to unexpected problems – these are just some of the reasons why science is challenging and yet very rewarding.

Working on a project as large as ZEN adds an additional level of complexity in both coordinating large teams of people distributed all over the globe. This summer I will be travelling to Japan to work with the ZEN partners in both Akkeshi and Hiroshima. It is an amazing opportunity that not many undergraduates get to be a part of. I am looking forward to all of the challenges I will be facing this summer. I’m sure there will be more than a few but, if I’ve learned my lesson, tangled fishing lines will not be one of them!

Chris is a rising senior at San Diego State University pursuing his bachelor’s in biology and Japanese. Before starting the ZEN program Chris worked with Dr. Violet Compton Renick on her dissertation research examining the interactive effects of parasites and pesticides on killifish behavior. During the SDSU ZEN course Chris led a feeding experiment where he measured the grazing rates of several different types of San Diego mesograzer. This summer Chris will be traveling as part of his ZENternship to Japan to assist Drs. Massa Nakaoka and Massakazu Hori.

Tsawwassen – home to big isopods, eelgrass and crabs

by Danielle Hall (College of William & Mary undergraduate student, ZENtern)

After three days of intense lab preparation and field work, the first ZEN2 site has been completed!

I arrived in British Columbia late on May 15th and the next day we got straight to work. After prepping materials in the lab we hopped in the lab truck and headed to our field site in a town outside of Vancouver called Tsawwassen. This particular site is in an intertidal zone and we chose to work on the lowest tide of the year since, during any other time, the site would be submerged and difficult to access.

To get to the site we climbed down over two hundred steps. Next, in our fashionable rubber boots, we hiked our way through the mud to get to our site (a treacherous task since the mud had a habit of clinging to our boots). On more than one occasion help was required to extricate a sunken foot.

I was amazed at the size of the Zostera shoots. They were nearly twice the size of the eelgrass in my home field site in Virginia! Not only were the shoots large, but the isopods were comparatively gigantic as well.

I was joining on day two of the field work and so the 20 experimental plots were already marked with orange flags. On this day, our job was to deploy the predation assay. The purpose of this assay is to understand the relative predation rates across the different ZEN site. The experimental units, or ‘PTUs,’ consist of a piece of bait tethered to an acrylic rod. The baits ranged from local animals, like the giant isopods, to a standard control, a piece of cut dried squid. A PVC quadrat helped visualize where to place our PTUs.

Having spent several summers helping deploy previous ZEN projects in the Chesapeake Bay, I was very curious to discover the differences in eelgrass beds between the two coasts. Here, anemones abounded right on the eelgrass shoots. I was amazed that they were able to make a living on plant tissue since in all my past experiences I had only ever seen anemones attached to a hard substrate (There are anemones living in eelgrass beds in the Chesapeake Bay as well, but they are generally small and scarce.)

Our lab group got particularly excited about a pair of nudibranchs who then became the stars of a Hollywood-esque photoshoot. Meanwhile a bald eagle joined us for a bit, clearly finding a tasty meal within the seagrass.

Our second day in the field was filled with surprises. After recording the results of the predation assay (the bait was either gone – eaten, presumably – or present), we continued with collecting samples. After combing through the plots at least two times, Celine – another ZEN participant – uncovered quite a surprise: a huge Dungeness crab hiding in the mud! And he was not too happy that we were intruding in his home. One of the other women, Jemma, mustered up the guts to pick up the feisty crab, and we all gathered around to take a picture with our new friend.

Day two was a long afternoon of working in our plots. So long in fact that the tide decided to turn despite the fact that we still had half our plots to process. A race ensued. We were optimistic. The tide was persistent. We lost. I was in the process of taking sediment core samples when I noticed the tide line getting ever so close, though I was determined to finish. When I peeked over my shoulder, I decided I could finish three more plots. I didn’t even finish the one I was on. Soon water was rushing into our site.

I abandoned my own task to help others finish collecting algae. We developed an effective method of the two hand scoop, where we quickly ran both hands through the plot to work like a sieve. Soon the water engulfed our boots which was followed by multiple exclamations, but together we finished all the plots. Looking towards the shore, our samples and coolers were being carried by the tide. It took all our effort to traverse back to the shore, and on the way retrieve the heavy, runaway samples.

Danielle is a rising senior at the College of William and Mary. As a ZENtern she will be working with the lab of Dr. Mary O’Connor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, as well as back at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science with Dr. Emmett Duffy’s Marine Biodiversity Lab during summer 2014. She has been volunteering in Dr. Duffy’s lab for the past two years and is from Massachusetts. Aside from her passion for science, Danielle is an avid dancer.

The Adventure Begins

Dave Godschalk (second from the right) poses with Dr. Duffy (left) and the College of William & Mary ZEN class

Dave (second from left) and ZEN classmates survey seagrass in the Chesapeake Bay before beginning their ZENternships

by David Godschalk (College of William & Mary undegraduate, ZENtern)

On my very first day of the ZEN Seagrass Ecology course at the College of William and Mary, I learned perhaps the most important lesson of the class, if not my scientific career. Our professor, Dr. Emmett Duffy, stood in front of our class and said these striking words:

“Things will not work out. You will mess up. Experiments will go wrong… Science is like that. The key, as an ecologist or any scientist for that matter, is to be able to adapt to those situations – to be creative and turn failures into successes. If you can do that, you will be successful not only as a scientist, but also as a person.”

As a geology major in an ecology class, this struck a chord with me. While I can go on and on about the structural and material properties that govern the Earth, different types of sandstones, and all those things near and dear to geologist’s hearts, I was out of my element in this course and I knew it. A fish out of water, one might say!

Those words on the first day are what saved me and I am so glad they did. Since then I have absolutely fallen in love with seagrass – the environment and the dynamics which govern the system. Even that particular seagrass-mud smell has grown on me. I will be writing entries for the ZEN Blog throughout the summer and one of my goals is to share with you my fascination with this unique environment. I hope to inspire you to feel the same way I do about this precious habitat and unprecedented project.

The Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN) is a collaborative, global study to examine what affects seagrass, and what role in turn seagrass play in coastal environments. What makes this project so unique is: (1) standardized experiments are performed worldwide, when often experiments in science can only be performed locally or regionally, and (2) undergraduate students (like me!) are sent to these global sites to practice and hone skills learned in class and contribute to the overall scientific study.

This summer I will be contributing to the ZEN research efforts in Zadar, Croatia, located across from Italy on the Adriatic Sea. It is a beautiful place and I am unbelievably excited to get things underway here. I will update you soon on how the experiments are going!

Dave is a graduating senior at the College of William & Mary and will be working with Dr. Claudia Kruschel in Croatia. His major is in geology with a marine science minor. Prior to studying seagrass ecology, Dave worked for Dr. Mark Patterson at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science on autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) and completed an honors geology thesis. His favorite class at WM was structural geology – and rock climbing. When not snorkeling in the seagrass beds or surveying rocks he can be found running marathons.

Science boot-camp at the Bodega Marine Lab

by Julie Blaze (UC Davis undergraduate, ZENtern)

Marine biologists don’t often find themselves trekking through dense remote jungles or climbing desolate mountains to conduct their research. Some would say we’ve got it pretty easy – the ocean covers around 70% of the earth’s surface, and studying biodiversity can be as easy as walking out to the coast and digging in the sand. The only downside to the job is that we are captives to the ebb and flow of the tides. My classmates and I in the ZEN class at UCD found that out the hard way when we took a field trip to the Bodega Marine Laboratory to survey the eelgrass growing in Bodega Harbor.

As someone who enjoys sleep, I can honestly say it is difficult to wake up at 5:30 am for any reason. Awake before the sun and trudging across the mud flats before its first rays had even reached the water, I know I wasn’t the only one thinking of the warm, comfy beds we had left behind. My boots were a little too big and kept getting stuck in the mud – I almost went sprawling face down into the mud more than once. As the sun rose, I wondered what we must have looked like to anyone watching from the shore – a zombie-like group of college students floundering in the mud. Slowly we gained more energy and set about surveying a large expanse of the seagrass bed collecting samples and taking measurements. We worked efficiently and conversation picked up as excitement and adrenaline grew with each new discovery and lapping reminder of the incoming tide. At first glance the mudflats and seagrass meadows look barren, but we quickly found that they teemed with life. Critters clung to the grass or buried themselves in the mud – making this eelgrass bed, similar to other seagrass meadows, one of the most diverse ecosystems in the ocean.

After a few hours the water had crept too high for us to work and we headed back to the lab to begin processing our samples. We put in a long day, getting as much done as we could before calling it quits. We all found those cozy beds soon after a late dinner, with the promise of another early field day tomorrow.

The next morning we again rose before the sun and stumbled out into the mud. But this time we were more familiar with the science – the methodology and how to work as a team – and we finished before the water chased us out.

By the end of the weekend I was thoroughly exhausted, but I didn’t care. We had spent an incredible weekend having an amazing adventure. Not only did I learn about the animals and ecosystem we were exploring, but I also learned several things about myself that weekend. First, I learned that I am willing and able to wake up before the sun to do research. Second, not even the wilds of a remote jungle can tempt me away from the mysteries of the ocean. And, finally, one lesson I will never forget – it’s easy to stay awake once your boots flood with freezing cold seawater. But, it’s even easier when you’re also out exploring a location as interesting as a Bodega Bay seagrass bed!

Julie is a graduating senior at UC Davis majoring in Biology. This summer she will be a ZENtern working with Dr. Nessa O’Connor in Ireland. Julie is a true team player and earned the nickname “den mother” during the 3-day, marathon class field trip and subsequent weeks of sample processing back on campus.

Photos contributed by Aaron Goodman.

Importance of knowing how to communicate science

by Jessie Viss (College of William & Mary undergraduate, ZENtern)

My bags are packed, my first hostel booked, and a pretty decent travel playlist has been downloaded to my iPod—I’m just about ready to head off to Portugal to work at the ZEN site there. Before this semester I didn’t even have a valid passport, and the farthest from home I’d ever been was when I left California to go to school in Virginia.

Needless to say I’m pretty excited about the prospect of spending two and a half months in Faro. The funny thing is, while I’ve always had a burning desire to see the world, that isn’t what’s got me practically giddy with excitement. No, what I’m most thrilled about is actually the work I’ll be doing this summer.

Throughout last semester we learned the methods for the different experiments that’ll be done across all the ZEN sites over the summer. While getting to go into the field made that class by far my favorite, the frigid waters made it so that the stars of the show were pretty scarce. But now we have the opportunity to really put into practice the procedures we’ve learned, to gather data that might test the theories of the papers we’ve read, to play a very small role in research that is of growing importance given the global trends indicating a decline in Zostera marina, so on the eve of my departure I think I’m within my bounds to geek out just a little.

My mom, on the other hand, is somewhat less enthused. Don’t get me wrong, she’s proud of me as only a mother can be, but is fairly uninterested in the scientific implications of the research. She’s been telling people I’ve landed an internship that has me spending my summer watching the grass grow. No attempts at explanation could convince her to phrase it any other way until one day the parents of a girl I went to elementary school with came into the restaurant where she works. They got to talking with her, and mentioned how their daughter also had a summer internship, working to preserve salmon populations in the delta that dominates the part of California we come from. Suddenly “watching grass grow” became an inadequate explanation, and when she got home mom asked just what exactly I’d be doing.

“Well there’s the podsicle experiment for one,” I began, “See, we take a small rod with a tether tied to it, glue some bait and put them out in the field for 24 hours.”

“Wait, what do you glue to these…popsicles…?”

“Podsicles, because we glue amphipods—little bug like things—to them to test relative predation rates,” I explained.

“And then what? Leave them out there in the water to get eaten?”

“Well—“

“So while Regina is out there saving the fishes you’re going to be gluing bugs to string??”

“Mom no, that’s not it. We’re testing how much predation there is at each site and perhaps the relative impacts of top-down processes—“

“I just can’t believe I raised a little mad scientist. Sure, now it’s just sea bugs, but how long until you’re in a white lab coat laughing maniacally and gluing people to rods.”

She was kidding, but has since gone back to telling people I’ll be watching grass grow. Seagrass, Mom. Maybe through my blog posts, and by the time I return from my ZENternship, I’ll be better able to show her the importance of the work I’m contributing to this summer.

Jessie is a rising junior at the College of William and Mary. She will be working with Dr. Aschwin Engelen in Portugal for her ZENternship this summer. Jessie is originally from California and this summer marks her first time traveling abroad.

Jessie was on the plane to Portugal while this post was undergoing final revisions, so, Jessie’s mom and parents of all of the ZENterns, this one’s for you:

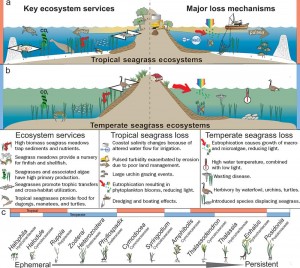

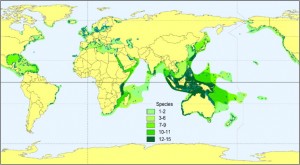

Seagrasses are diverse and found all over the world (image courtesy of Short et al. 2007: Global Seagrass Research Methods)

“Seagrass beds are an important, valuable, and widespread habitat that provide many important services to humanity. They contain many different species of plants and animals, including fishes and crabs that one day will end up our dinner plates. They help soak up the excess nutrients from fertilizers and waste that find their way into coastal waterways. Seagrasses also hold the soil together, which prevents erosion and lessens the impacts of coastal storms. They even help combat the effects of global climate change by capturing carbon, preventing it from accumulating in the atmosphere. As such, it’s vitally important that we understand what factors promote healthy seagrass beds.

The purpose of the Zostera Experiment Network is to, quite simply, understand how seagrass beds work. We will measure a suite of variables – some of them related to the environment, like temperature, salinity, and location, and some of them related to biology, like the number and diversity of animals found in the grass beds. We will relate these variables to inform our predictions about how seagrass beds function. By partnering with institutions all over the world, we can evaluate these predictions generally. ZEN represents an unprecedented effort to link process to function in a coastal habitat. Ultimately, the information obtained from ZEN will aid us in protecting and globally conserving this ecosystem, so it can continue to provide the services listed above.”

A test worth taking

by Ellie Marin (UC Davis undergraduate, ZENtern)

Exams are inherently nerve-wracking. First there’s the main concern – did I study enough? Did I study the right material? And then there are other details – I have nightmares about running out of ink in my pen, accidentally missing questions on the back side of an exam

page, or even forgetting to write my name on the top of the exam paper. But, one thing I’d never feared was being stalled by accidently super gluing my hand to the exam paper itself. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from the Seagrass Ecosystem Ecology course taught by Drs. Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz that I’m taking at UC Davis, it’s to be prepared for the unexpected.

Ellie (left) and classmates conduct research at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory for the ZEN undergraduate course in Seagrass Ecosystem Ecology

This hands-on field methods course was designed to educate the undergraduate students participating in the ZEN research (the “ZENterns”) on the methodology, theory, history, and purpose behind seagrass ecology and the Zostera Experimental Network. Our class featured a weekend trip to Bodega Bay, California to conduct field research, student presentations of papers from the primary literature, lectures, and group research activities. Today’s lab practical exam was intended to assess how much we learned from all of the different aspects of the course. In preparation for the exam, I read through my notes. It is a fairly hands-on class, so I wasn’t exactly sure how to study. Chatting with my 11 classmates revealed that we were all in the same boat.

UCD ZEN students perform the class practical exam, which involved answering questions on the course subject matter as well as demonstrating skills developed during the course.

Similar to other laboratory courses, our class practical featured a written portion as well as directed questions from a series of different stations setup around the laboratory. After a timed 30 minutes to complete the 5 pages of short answer questions, I started on the first lab station and the clock ticked down for us to rotate every 5 minutes. Some stations had microscopes with animals under them for us to identify and others materials for us to perform targeted lab skills. I glanced upon the familiar mesograzers under the scope, stumbled through some exotic amphipod identification, measured eelgrass shoots, and even wrote a haiku about epiphytes. The 5 minute periods per station rushed and rushed. I scribbled until the last second. And then I got to one station that fortunately, didn’t involve writing. Yes! Something I’ve done before! “Tether an isopod. Next, tether an amphipod.” We’d done this during our field trip at Bodega Bay to assess predation rates on mesograzers in the field. I got out the glue, set the line, caught the mesograzer. I was all set. No tricks. No doubts. I just had to tether the little guys. But this time it was different.

When we tethered the animals on the field trip, our instructors did not time us. This time I was racing against the clock. I quickly trimmed 20 cm of fishing line for the tether and began tying the proper knots to secure it. It wasn’t this difficult before! This line seems different! The sweat on my hands is not helping! After finally succeeding in tying an appropriate knot, I trimmed the line down and began looking for my first bug. I spotted one and bypass the forceps to plunge my hand into their housing container. I gently grab an isopod and place him on a paper towel to dry off. He’s sedentary. Good news. I grab the glue and squeeze a blob on the knot in my line. The next part is tricky. I have to glue his line – his crustacean leash – right onto his back. Success! After getting it to stick, I put the little guy into a water cup and watch him swim around with his little line in tow.

I’m half done now! I next set my sights on the amphipod. In the heat of the exam, I forget the order of the tethering process and plunge my hand into the container to grab the only amphipod I see. It’s a lively gammarid who undulates all over the paper towel, nearly off the table. This isn’t right! I put him back in the water. Focus! I grab the line and begin to cut to 20 cm again. The knot tying frenzy begins. Just go slow. I make a proper knot and grab the glue. It’s not coming out! I squeeze the glue harder than usual until a thick blob encases my knot… it’ll do. I grab my lively amphipod and he begins twisting and spinning – he’s expected me this time. I use a dropper to drip water on him as he lays on the paper towel. This appears to have a calming effect, and he ceases his tantrum. Now the tricky part. The isopod was big, but this guy is small, just under 1 cm in length. I have to get the glue right on the middle of his back or I risk injuring him. I go for it and miss, somehow getting glue all over my fingers. My fingers start to stick together. I unstick them and attempt to refocus in order to finish out this station – I know I’m almost out of time.

I rearrange my station for better focus, and this involves moving my exam out of the way. Big mistake. I have glued my hand to my exam. I rip the paper off, revealing a thumb and palm covered in ripped, sticky white paper. The timer goes off and I put my amphipod that wouldn’t get tethered back for the next student. “Next Station.” The test continues with new, equally challenging tasks and I proceed, with the paper still glued to my hand

Drs. Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz (left) demonstrate amphipod tethering during the class field trip to the Bodega Marine Lab

The exam was hard. Not because I was underprepared – there are some things in life we can never prepare for. It was not unfair – I had either seen, performed, or learned everything on the exam. It’s not that there wasn’t enough time – everything in life has a time limit. The exam was hard because I have never had so much expected of me in a college class. Our instructors believe that we can do far more than simply answer A, B or C, or regurgitate a paragraph that we memorized from our notes. Our instructors dare us to reveal what we can actually contribute to science. They challenge us to be creative, resourceful, and clever. The point was to experience the exam, not just complete it. Success in research can be measured in how well we perform under stress. Things may not go as planned, but at the root of ecology is evolution, and we must all continue to adapt. This involves accepting our failures, building on our strengths, and focusing on how to move forward.

Some amphipods are meant to be free. Some tests are meant to be stressful. And some hands are meant to be glued.

Ellie is a rising senior at UC Davis pursuing her bachelor’s in biology. Her favorite aspect of the ZEN course was the exposure to field research, and her favorite experiment involved tethering amphipods to test for predation in the Bodega Bay seagrass beds. Her dream job is to be a science communicator and educator. She will be traveling to Ireland and Oregon to assist with ZEN research this summer with Drs. Nessa O’Connor and Fiona Tomas Nash, respectively.

Photos contributed by Aaron Goodman, Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz.