A swim down memory lane

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN coordinator)

The past several months we’ve been entrenched in finishing processing the experimental samples, analyzing data and writing up the results. This is a big switch from our constantly on the go routine during field season, and gives us time to reflect on what an amazing past two years we’ve had with ZEN. In that vein, I’ve dug up two pre-blog posts, quick little snippets I wrote back in the summer of 2011 before we launched the ZENscience.org website.

August 2011: Fieldwork Happens

Out in the field, the one thing I dread most isn’t encountering sharks in the murky water, seeing lightning streak overhead, or being pursued by voracious horseflies. Nope – it’s Murphy’s Law. We’ve all experienced it. A perfectly planned experimental setup can go from a well rehearsed orchestra to utter cacophony in a split second simply because someone forgot to bring scissors or dropped the ruler overboard, or a rogue wave made off with a pencil.

In our case, after placing and pounding 320 poles in the water we realized that our once lovely Zostera bed is now overgrown with Ruppia, a different type of seagrass. In our defense, the seagrass in the clearer water near the approach to the site was, in fact, Zostera. Murphy rears his ugly head, once again. How to deal with the mishap? Remove the poles, all 320 of them, call a few colleagues to find a new site, borrow a boat, and start over. This time everyone knew the drill and the setup went exceedingly smoothly. And, in the process we all learned how to distinguish the three local types of seagrass (Zostera, Ruppia, Halodule) by touch alone in the murky water. Turning Murphy into an educational experience – now that’s science! Having a team of graduate and undergraduate students who keep smiling? Priceless.

[Update: While I still despise coming up short on cable ties in the field, getting caught out on the water during a thunderstorm has quickly risen to fear #1. See the "Science is electric" blog post from 2012 to find out why.]

April 2011: When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight

In preparing for ZEN the VIMS team became well versed in navigating international shipping. One of the things we learned early on was that customs agents are often quite literal. For instance, “300 blocks of 120 mL hardened dental plaster” can be translated into medical equipment and is subject to high tariffs. Doesn’t matter that the plaster has already been hardened and can’t be used to make casts of someone’s teeth – it’s all in the product description. And being vague isn’t much help either. Some countries want to know the composite materials of a t-shirt or line items of every ingredient in the dog food we used as fish bait, while for others the phrase “for education/research, not for resale” is sufficient. We are expecting that to some extent each country will have unique mesograzer assemblages and ecological interactions – why should we assume their import/export process to be the same?

[Update: I wrote this after a week of playing phone tag and emailing with shipping and customs agents to get our packages cleared and on their way to our international partners. Ultimately everything went through and there were no major delays or disruption of our partners' field schedules. Lesson learned? Leave at least a 3 week shipping allowance for international projects. And, keep UPS on speed dial!]

Memorable moments in Virginia

by Katelyn Jenkins (College of William and Mary undergraduate student)

Many of the jobs I’ve tackled this summer have surprised me. I would not have guessed that I would become a PVC cutter, plaster block-maker, wire bender, mesh cutter, or sewer. However, I have learned that it takes a lot of skills, laughter, and water (often with a dash of Gatorade!) to prepare for such large-scale experiments in marine ecology. Through spending days of cutting many pieces of PVC and the messy job of making plaster blocks, I have enjoyed this job because of the new friends I have made in the MBL lab. From having numerous nicknames to help distinguish myself from the lab’s REU (also a Caitlin), to dancing on poles marking experimental cages in the field, this summer has been a great one to remember.

When I am not counting PVC or cutting wire, I have taken over the job of transferring seagrass samples from various ZEN partner sites to reinforced vials to grind down for nutrient (carbon and nitrogen) analysis. To do so, I have to go to William and Mary’s main campus to use a machine that will grind the samples (affectionately known as “Shakira” by its owner, Dr. Kerscher, who graciously allows us to use his lab space). The first few times I went to the main campus to grind the samples, the machine was placed in a lab. However, all of the large samples from partner sites makes for a very tired and warm ‘Shakira’. To resolve this, I planned to take breaks between sample grinding during my next visit. But, when I arrived on campus weeks later in almost 100° F weather in my shorts and t-shirt, I had no idea the machine was being moved to a cold room of 34° F! Though the initial “air conditioning” felt much needed, I quickly found myself freezing (literally) while trying to grind my samples. With multiple “defrost-Katelyn” steps inserted into the protocol (which involved running outside into the muggy Virginia heat until my fingers had thawed), I was able to successfully grind all of the samples. I can now say that I always come prepared with full gear to face the cold room. You can easily spot me walking across campus as I am the only one with a big jacket and pants in the middle of summer!

Aside from the strange climactic working conditions, I spend a lot of time in the field – one of my favorite parts! I have learned to master “Snorkeleese”, the language when talking with a snorkel in your mouth and your face down in the seagrass bed. “Ooo uoooo eeeddd elpppp?” translates easily to “Do you need help?” and “ablee eye eeese” almost always means “cable tie please”. All joking aside, most importantly I have had the chance to snorkel in the Goodwin Islands and see tons of marine life, all while learning the ins and outs of getting experiments set-up and broken-down in the field.

After taking a Marine Ecology course at William and Mary, it has been very exciting to see a lot of the things that I have read many papers on. For example, I read many papers on seagrass beds and algal blooms in the Bay and it is very interesting to see these different topics hands-on. One of the most interesting experiences I have had with marine life during the ZEN project was during the break down phase. While riding from our field site back to VIMS, about 15 dolphins began to swim around us as they searched for food. It was very exciting to see these animals so closely, especially because I have never seen so many in the York River before! Aside from this, I have had the opportunity to see tons of crabs, fish, and even sting rays!

Overall, this summer has been an incredible experience that has taught me many valuable skills. I can’t wait to see what lies ahead!

The business of science

by John Schengber (VIMS undergraduate student summer intern)

I am an undergraduate at James Madison University and have been working this summer with the ZEN team at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in Gloucester, Virginia. I have lived right across the river in neighboring Yorktown for most of my life. Surrounded by nature and adventure, I have become an outdoor kind of guy with an intense curiosity and respect for nature. I still have not decided the exact career path I want to take, so this summer was an excellent opportunity to explore research and marine biology.

I think most people in the lab were surprised when I revealed that I am in fact a business major. Everyone else around here studies (go figure) science. In the fall, I will be returning for my sophomore year at James Madison University, where I am pursuing a major in International Business coupled with a double minor in Spanish and Environmental Science. Now, why in the world would a business major be working in a science lab? First, let me emphasize that this career direction is not entirely definitive for me. I am fascinated by a myriad of fields of study. In business, I am drawn to the ideas of entrepreneurship and creativity, but not so much to the possibility of cubicle entrapment. I dream of running my own company, but am conflicted as business/industry can often be a driving force in the destruction of our natural world.

My love for science stems from my love for nature and the questions it begs us to answer. I am in constant awe of its wonder, and my life would be at loss if my studies lacked a good dosage of the biological sciences. Yet I love to interact with people (especially in Spanish), to solve problems, and to try new ideas in the business sector. So, I have come to a crucial intersection of interests. Business seems to be the last thing to enter if one is focused on saving the world from its own ruin. But I wonder if it can be done differently? Can we make a business that is not just sustainable but truly symbiotic with our environment? Most importantly, can this venture be profitable in a cut-throat capitalist economy? Lastly, can I be the person to do this? I have no idea. But I’d say it’s worth a shot.

So here I am at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science taking that first step. I came into this position with a few hopes and expectations. I wanted to check out the work of a marine biologist, which is my greatest love in science and the field that I would most likely enter if I decided to pursue a research career. I hoped that I would meet some incredible people with inspiring intelligence and personalities to match. I wanted to view the process of scientific investigation from beyond classroom instruction or media coverage. I wanted to learn a lot and experience even more. But really I just wanted to hang out with some amphipods.

All of my hopes and expectations have been fulfilled, and I have loved every minute of it. I have made new friends and linked up with old ones (see Nicole Rento’s post, fellow lab member this summer and best friend since, well, forever). I have learned more than I could have ever imagined. I have spent some quality time with lots and lots of amphipods. And I’ve learned that running a lab really isn’t too much different than running a business. There are budgets, deadlines, management, and lots and lots of ingenuity. Maybe there’s hope for me yet.

Melding biology and economics, an undergraduate perspective

by Nicole Rento (undergraduate student at Brown University)

My name is Nicole Rento, and I have been working at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in Gloucester, Virginia with the ZEN team here this summer. I was born and raised in Virginia about 30 minutes away from VIMS in Newport News, where I attended elementary school through high school with fellow lab intern John Schengber. In a weird twist of fate, we both ended up coming home from our first year at different colleges (him at James Madison University and me at Brown University) to work in the Marine Biodiversity Lab. It’s been great working with one of my oldest and best friends, and making new ones here at VIMS.

I just finished my first year at Brown University, and I absolutely love it. I even enjoyed waking up at 6 A.M. most mornings for varsity swim practice, working in the library until late into the night, and especially everything in between. Heading off to college, I was really considering going into the field of medicine. Growing up with two surgeons as parents and listening to their work-related dinner conversations for 18 years, it was hard to imagine doing anything else with my love for biology.

Throughout my first semester at Brown, however, I began to move away from my thoughts of becoming a physician and the idea of having to take two semesters of organic chemistry and towards my love for the environment and ecology. And surprising myself by thoroughly enjoying an introductory economics class during the spring semester, I put myself on the path of double majoring in biology and economics. As to where that will take me, I’m not so sure. At the end of the semester I did know that I wanted to start figuring that out.

My advisor at Brown (Dr. Dov Sax) knows Dr. Duffy and put me in contact with him. I was delighted when he graciously and enthusiastically offered me an internship here in his Marine Biodiversity Lab. So here I am! I started in May, not sure what to expect nor whether I’d be able to see a path to integrate my two passions (biology and economics). I was introduced to the ZEN project on the first day, and have been working on different aspects of the ZEN projects every day since. The ZEN postdoctoral researcher Pamela Reynolds and the lab manager here Paul Richardson started off familiarizing me with the species we would be working with this summer. I learned about the biology and ecology of Zostera, the seagrass around which the ZEN project is formed, and all the animals that live within the habitat it forms including blue crabs, pipe fish, amphipods, gastropods, and isopods, to name a few of my favorites. I never thought I would see so many ‘bugs’ in one summer, let alone count and sort all of them. I’ve gotten pretty speedy at identifying these small invertebrate algae eaters.

I also never thought that I would become so experienced with PVC piping. One of my first tasks was to help Pamela and Paul design the cages for the predator exclusion portion of the project. Another unexpected job: John and I teamed up to make hundreds of plaster blocks for another part of the ZEN project. There were other tasks such as cutting circles of plastic Vexar, and bending hundreds of wires to be placed in the drying plaster blocks. Plaster, PVC piping, Vexar, wires… all for ecology? Yes. Although the connection was hard to find sometimes, as the cages and materials began to take shape, so did my first lesson in ecology: data don’t come out of thin air. First you have to collect those data, and to do that we had to run an experiment. That step came with trips out into the water – field days. I participated in both the set up and breakdown of an experiment to measure the effects of small predators (crabs, shrimp, fish) on seagrass communities. Working under the sun, holding your breath as we worked to secure our cages in murky water, it was no easy task. But seeing those 30 cages, all designed and built by the lab, helping us answer the important questions we ask with this project, was a feeling of incredible accomplishment for me and for my fellow lab members.

After running the experiment there comes countless (often tedious) hours of sample processing. My initial training in identifying seagrass species has come in very handy as we begin examining the final communities from our experimental cages. Finally, after the samples are sorted and the data collected, they have to be analyzed. But we aren’t there yet. I can’t wait to hear the stories from the other sites, and to see what happens as we begin to go through the data from our site’s experiment.

This summer has been a wonderful experience filled with bugs, PVC, great scientists and great friends. Working at VIMS this summer has not only reaffirmed my love for biology, but it has given me insight into the combination of biology with economics. During the summer I heard about other projects that had taken place in our lab and in others. One example was the research our lab did with algae as a biofuel. By running river water through giant flow tanks and back into the river, algae was able to grow on the tanks and remove excess nitrogen and phosphorus from the river water as it ran through the tank, returning cleaner water into the river. The algae could then be harvested and used as a biofuel. Not only is this a breakthrough biologically, but economically as well. In theory, if companies were to install these flow tanks in their factories, they could not only create their own naturally cleaner biofuel, but also help to clean river or lake water. Although still in the preliminary research and development phase, projects like these are beneficial to both the economy and to the environment, and I can definitely see myself being involved in similar projects in the future.

I’m so thankful for having the chance to work with the VIMS Marine Biodiversity Lab this summer. Good luck to the other sites!

Fieldwork is never boring

by Serena Donadi (ZEN exchange fellow in Virginia)

One of the most exciting days in the field was when we installed cages for an experiment examining the effects of predators (shrimp, fish, crabs) on the seagrass comminity. After spending many days cutting PVC pipes, sewing meshes and gluing parts together, our cages were finally ready! The plan was to go to the experimental site (Goodwin Islands), pound 60 poles into the sediment and attach our cages to the poles with bungees and cable ties so that the currents wouldn’t drag them away. Plus, to make the cages sink to the sea bottom, we planned to put few shovels of sand inside each mesh.

The cages are basically empty cubes (sides of about 0.5m), made by PVC poles, which are enclosed in a mesh bag. Inside the cages, seagrass communities are recreated by adding mesograzers (gastropods and crustaceans such as amphipods and isopods) and seagrass shoots attached to a plastic screen. The aim of the experiment is to keep all predators (fish and crabs) outside and see what happens… Will the populations of grazers increase? How will such an increase affect the algae and seagrass? Do we see evidence for a trophic cascade, where animals at top trophic levels promote plants at lower trophic levels by controlling species at middle levels?

The weather forecast that day was not very optimistic and there was chance of thunderstorms. We decided to give it a try and started loading everything we need on the boat. The boat was literally full! I wish I’d taken a picture. After adding 10 buckets full of sand, lots of poles, coolers with seagrass and other field. I was really afraid we would sink. But our captain for the day, Kathryn, carefully directed us as to how to load the boat to balance the weight and we were safely on our way. Once we arrived at the field site, the bad weather started rumbling and dark clouds were quickly moving in our direction. I have been in Virginia for more than one month now, but I am still surprised by how fast thunderstorms can appear here and how strong they can be. We decided to quickly head towards a sheltered dock nearby and wait for the storm to pass. After one hour we were back in the field.

It’s odd to say after so many days of terrible heat, but the water was chilly! I was glad I had my wetsuit with me. The sea was still quite rough making the fieldwork quite challenging. To be able to attach the cages to the sea bottom, I wore an incredible heavy weight belt. Despite it, the drift of the waves could still make me roll on the bottom as I snorkeled. The water was so murky that I was not able to see what my hands were doing. Sink to the bottom, stretch my legs to avoid rolling, bind the bungee around the cages and secure everything with cable ties.

After a few hours all of us were trembling because of the cold, the tide was rising, and dark clouds began to cover the sky. Finally the last cage was placed and we jumped on the boat. The sea was stormy and Captain Kathryn did an awesome job in bringing us back to the VIMS boat basin where we store the boats. On our way, heavy rain poured from the sky, hurting on our skin and blinding our eyes. I put on my diving mask and thought how ridiculous I should look wearing a mask and a wetsuit outside of the water. Eventually we arrived at the boat basin, tired, hungry and cold.

That night as I lay in my bed and thought about the day, I realized how lucky I am for having this great chance to work with wonderful people in this amazing ecosystem. It was so much fun! Really, it was one of my favorite days so far in Virginia.

Student profile: REU participant Caitlin

by Caitlin Fikes (VIMS summer 2012 REU student)

Greetings, fellow sea-lovers! My name is Caitlin Fikes, and I’m thrilled to be part of the ZEN family. I am an undergraduate student participating in the National Science Foundation’s REU (research experience for undergraduates) program this summer at VIMS. I’ve been asked how I became involved in the ZEN project and the type of background that makes for a competitive REU applicant. To answer that, let me tell you a little about myself.

I was born in the fine state of Virginia, although for all intents and purposes, this summer was the first time I’ve been here. Growing up my family felt the need to move when the wind changes; we breezed through Virginia and onto another state before I was old enough to remember a thing. I grew up in various states, and developed a love for change and travel and new experiences. I’ve never regretted my vagabond childhood for an instant, and I don’t intend to ever stop moving.

I have always loved nature and wildlife. As a child, I read every book on animals that I could get my hands on, and spent my days traipsing through the woods looking for snakes or deer tracks. But I didn’t know what direction I specifically wanted to go. I loved all nature, all animals, everywhere. When I was fifteen, I acquired my SCUBA certification, and it became very clear to me that I belong in the marine world. I resented the human limitations that required me to eventually come back to the surface for air. I would have remained underwater forever if I could, exploring and observing quite happily. My dream of becoming a marine biologist was born.

Other than obtaining the SCUBA certification itself, I took my first real step towards my dream in 2009, the summer before my senior year of high school. My family was living near Omaha, Nebraska, at the time, and the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha was offering a summer “Eco-Adventure” course. The program consisted of first working with various animals at the Zoo for two weeks, and then culminated in a week-long trip to Cozumel, where the group would be researching coral reefs and snorkeling alongside migrating whale sharks. Barely able to contain my excitement, I applied and was accepted. Caring for a myriad of different animals at the Zoo was extremely informative and fun, but when it came to my marine biology dream, the week in Cozumel sealed the deal for me.

An example of the goby and shrimp pair (courtesy: Operation Pufferfish). To learn more, check out this NY Times page

And it wasn’t just about the charismatic megafauna; the dolphins and whale sharks were fantastic and all, but the highlight of the trip for me was discovering a tiny shrimp/goby pair while diving on the coral reef. I had read about the mutualistic relationship shared by shrimps and gobies, in which the blind shrimp digs a burrow for both to live in and the goby becomes a lookout and bodyguard. I thought it was incredible. To see a pair in the wild was exhilarating. The entire experience felt like a green light to pursue this ambition.

As soon as I returned from Cozumel, I used my connections from the program to obtain a volunteer internship at the Omaha Zoo’s Scott Aquarium. Throughout my entire senior year of high school, I spent every available hour at the aquarium, caring for and learning about the animals there, as well as observing the aquarium’s ongoing research. I learned that the Scott Aquarium was one of the first institutions in the world to successfully raise sexually produced elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) polyps, a very important and highly threatened species of coral. To be so close to the cutting edge of marine biology research was an awesome opportunity; but I was eager to actually jump in and get my feet wet.

I began my college career at the University of Miami in 2010, double majoring in biology and marine science, and double minoring in chemistry and environmental science. Miami has given me a thorough grounding in biology, chemistry, and physics, with emphasis on marine science and exposure to incredible field and research experience probably not available to universities elsewhere. By the end of only two years as an undergrad, I had participated in field studies in coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests. I had helped catch and attach satellite tags to pelagic sharks. I had even started my own research project looking at the effects of a common herbicide on the embryonic development of sea urchins, which I will be continuing in the fall. And, in my spare time, I became certified to assist in rescuing stranded marine mammals.

Throughout this time, I also began to better define my interests and which direction I wish to take in marine biology. I became interested in marine conservation biology, especially in light of the current global fisheries crisis. But even more than that, I am interested in how changes in a particular species can affect the entire ecosystem. What is the nature and strength of the many connections between species? How does tugging one strand shake the food web? And how do the non-biological elements factor into the equation? I realized that what I want to become is actually a marine ecologist.

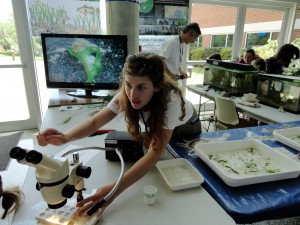

Undergraduates Nicole Rento (left) and Caitlin Fikes (right) prepare materials for a field experiment

Which brings me to this summer. Knowing that I wanted to do research, both to get more experience and to meet the people in my chosen field, I applied to the REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) program here at VIMS. I was surprised and delighted to receive a call from Dr. Pamela Reynolds. When she told me that she felt I was a good fit for the Marine Biodiversity Lab under Dr. Emmett Duffy, I was honored, ecstatic, and extremely nervous!

Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay are gorgeous, VIMS is an incredible institution, and the members of the lab are both great people and great scientists. I would love to be able to follow in the footsteps of the skilled scientists who came before me, and every time we go flying out over the York River to our field sites for another fun day of science and adventure, I can’t help but feel that I’m on the right track.

Ducking and dodging thunderstorms in Virginia

by Kathryn Sobocinski (VIMS graduate student)

I’m a PhD student at VIMS, co-advised by Drs. Emmett Duffy and Rob Latour. While my contributions to the ZEN project thus far have been minimal as I’m in the midst of writing up my dissertation research, I did get drafted into action last week when ZEN was in need of a boat driver and an extra set of hands… I qualified. My research focuses on trophic interactions of fishes in seagrass beds—not all that different from the focus of the ZEN projects this summer. What is different is how we think about these systems. I keep reminding the folks in Emmett’s lab that their definition of “predators” is what those of us in the fish world call “prey.” Or what fishermen would call “bait.” It’s all a matter of scale.

And so I found myself in the field with ZEN, and with a few firsts after 4 years of doing field work in Chesapeake Bay. Last week we had one of those early morning tides and correspondingly early start times that made me think staying in and writing statistical code was a good idea. The first morning the alarm went off at 4:30am. My dogs definitely did not want to get up, but they saw the swimsuit and towel as a good sign—they love the beach. Little did they know that today was not their day for a sunrise swim. I made sure I had enough adequate coffee to function, and was out the door. Standing on the boat with the sun rising, I remembered why early field work is so nice: calm water, fresh air, and, most importantly, it’s not so hot! We got to the field site, Pamela got us all organized (which admittedly felt a little like herding cats since several of us were new to the scene), and we set to work installing the cages for an experiment excluding ‘predators’ from patches of Zostera to examine their effects on the seagrass community. I had toyed with conducting a predator exclusion experiment for my own work, but in the end it fell to the wayside—so it was nice to see the set-up and be involved with the execution. We completed the first stage of the set-up before the tide rolled back in and the weather caught up with us.

One of the occupational hazards of field work in southeastern Virginia in the summertime is the random thunderstorm. As grateful as I am to our friends at the National Weather Service for providing quality marine forecasts, even they occasionally get caught with their umbrellas down and we all get soaked. Tuesday was one of those days. We decided to go in the field on the forecast of “morning showers, afternoon thunderstorms,” and again, we had an early start. We motored out to the site, anchored up, had one person in the drink, and then thunder rumbled in the distance. Once, twice and we pulled anchor and ran to our thunderstorm hideout, a picturesque marina at Back Creek on the York River. We tied up just as the skies opened and the thunder boomed overhead. After four years and almost constant, sometimes daily fieldwork in this area, I had yet to duck back into the thunderstorm hideout! Thankfully, there was a nice awning to keep us mostly dry and Pamela had brought some field snacks to keep us happy as we waited for the storm to pass.

After an hour, we were back onsite and installing the second part of the experiment: putting the eelgrass into the cages and populating the cages with grazers. The wind was building and without sun, the water actually was kind of…dare I say…cold! I hopped onto the boat to have a look at the radar (the beauty of smartphone technology!) and things looked clear, so we kept pushing forward, despite the ominous looking clouds over the northeast part of the nearby Mobjack Bay. Sure enough, the next time I checked the radar, 30 minutes later, multiple storms had popped up and things were looking ugly. We called it a wrap, but this time we had no sooner left the site when the skies opened up and pelted us with big, juicy, rain drops. If you’ve never been on an open skiff in pouring rain, you have missed out on the field spa treatment of “dermabrasion”—it feels like you’re being sandblasted! Ouch. While I prefer sunglasses in such conditions to protect my eyes, Serena decided a diving mask was the ticket for protecting her face— she definitely won the field fashion contest! Thankfully, it was just rain with no thunder and lightning, so we pushed on and docked at VIMS looking like a group of drowned sea rats.

By the end of the week we had finished installing the experiment, shored up any caddywampus cages, scrubbed the outside of the cages clean (anyone who owns a boat in these parts can tell you that things in the water get fouled very quickly), and generally made sure the experiment was set. We’ll hope for fewer storms as the experiment continues. While the sun can be hot around here in the summer, it’s much nicer when the wind lays low and the thunderstorms hold off until we’re safe in the lab!

Friendly people, stingrays and turtles: Welcome to Virginia

by Serena Donadi (ZEN exchange student fellow in Virginia)

My ZEN experience for 2012 has begun! Two weeks have already passed since my arrival at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and here is my preliminary evaluation: great people, great place and great work!

First of all, I was impressed by the welcome and friendliness of the people, from my housemates to the VIMS’ stuff. The research group of Dr. Emmett Duffy is composed by graduate and undergraduate students along with apost-doc and technicians working on different projects. What’s really great is the high level of collaboration and interaction within the group. Fieldwork means hard work, limited time (the tides rule our schedule) and often adverse climate conditions (40 degrees Celsius!), and everybody knows that one person can make the difference to successfully reach the goals of the day. Helping each other is also the best way to get to know what other people are working on. Collaboration is the perfect recipe for a highly dynamic scientific environment, and the Marine Biodiversity Lab and others at VIMS are definitely a good example.

What a great place is the Chesapeake Bay! The experimental site of the ZEN experiments this summer is really beautiful. Dense beds of seagrass cover wide areas along the coast and are inhabited by an extremely rich community of organisms. The first day I saw the place I felt a bit like Alice in Wonderland. I put my hands into the dense seagrass bed and I found them covered by tens of giant (at least according to my experience) amphipods, isopods, gastropods… I jumped out of the boat and started walking. Blue crabs (even bigger than my hands!) were hiding everywhere and quickly moved away from my feet. Schools of silversides followed me, maybe attracted by the disturbance and the potential for an easy meal as my feet stirred up the sediment and associated invertebrates as I walked through the seagrass bed.

The women of the ZEN team in Virginia: undergraduates Nicole Rento, Caitlin Fikes and Katelyn Jenkins, graduate student Serena Donadi, and post doc Pamela Reynolds

After collecting myself from the marvel and the surrounding beauty, I helped my team with the tasks of the day: collecting seagrass shoots andepifaunal invertebrates, and catching and measuring mesograzer predators (small fish, crabs and shrimp). With 5 people, we managed to finish before the tide was too high and we jumped on the boat, ready to go back. As a perfect end to my first day of fieldwork, a sting ray swam elegantly in front of us and the head of a terrapin (a type of turtle) appeared at the surface . Maybe they were welcoming me to Virginia, or maybe they were just relieved that we retreating away from their home. I prefer to think it was the former.

Now that I’ve got my feet wet, I’m excited for what other adventures await me here in Virginia!

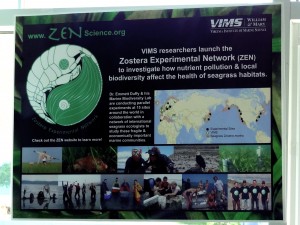

ZEN at Marine Science Day 2012

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN coordinator)

We introduced the Zostera Experimental Network to the public of Virginia at the tenth annual Marine Science Day (MSD) event at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in May, 2012. Over 2,000 people visited the VIMS campus in Gloucester Point, VA for a full day of behind-the-scenes learning about marine science and the Chesapeake Bay.

Our Marine Biodiversity Lab ran an touch tank exhibit titled “Secretive Seagrass Creatures” where kids and adults had up close encounters with mesograzers and the fish, crabs and shrimp that live in local seagrass habitats. We even hooked up a high definition video camera to one of our microscopes so everyone could watch an amphipod graze on algae and make a mucus tube.

The public was very receptive and inquisitive, especially regarding the ZEN.

Questions we were frequently asked:

Q. What do you mean everyone at the different ZEN field sites did the same experiment?

A. We shipped boxes of experimental materials and sent copies of a detailed protocol (a “how to” guide book), along with instructional videos, to all of the other scientists to ensure that everyone used the same methods. The videos were great as not all of the participating students from the other countries spoke fluent English.

Q. How can you compare the Chesapeake to somewhere like Norway or Alaska? Isn’t it colder up there?

A. Yes, it most definitely is! And this variability, or differences in environmental conditions such as temperature and salinity, is very important. By having a range of environmental conditions, we have more power to understand how these factors such as being in a colder or warmer place can affect the important seagrass communities we are studying.

Q. How do you know these mesograzers are important? They’re really small. Don’t turtles, herbivorous fish and other larger marine animals eat more?

A. Although mesograzers such as amphipods are small, they can eat a lot of algae, especially the algae that grows on the leaves of seagrass and competes with the seagrass for light and nutrients. We have conducted many experiments in tanks and have found that mesograzers can do a good job at keeping the seagrass clean and promoting its growth. While turtles and fish may have larger mouths and take bigger bites of algae, they aren’t necessarily eating the same types of algae or the algae growing on the seagrass, and these larger herbivores aren’t found all over the world. Mesograzers, however, are everywhere and can be very abundant. If you grab a big handful of seagrass in the Chesapeake you can catch hundreds of amphipods!

Q. I live near the Chesapeake. Why should I care about seagrass in Japan or Sweden?

A. By studying other places we can understand how regional and global issues such as pollution, overfishing and seawater warming can threaten our local systems. Oceans make up about 70% of the Earth, and most of them are connected. If we only study the Chesapeake, we loose a valuable opportunity to help understand and predict future challenges.

Our one shortcoming from this year’s Marine Science Day – no one dressed up like an amphipod or other mesograzer for the annual Parade of Marine Life, although while cleaning up our lab we did find a child-sized Idotea (a type of marine isopod) costume from years past. Next time!

Science – it’s electric!

By Pamela Reynolds (VIMS; ZEN Coordinator) with contributions from Paul Richardson and Akela Kuwahara

There are few times in my life that I can honestly say that I was terrified. Feeling the Loma Prieta earthquake in ’89, (nearly) tripping over a cottonmouth snake, taking my qualifying exams all stand out. So does the 28th of June in 2011.

It started out as a normal day, or at least as normal as a day of fieldwork can go at the ZEN site in Virginia. It began with the usual flurry of activity in the early morning packing the experimental equipment and loading the boat, checking the associated weather websites and filling out the float plan, slathering on sunscreen and pulling on life jackets and dive booties. It was a typical hot, humid, and sunny summer field day in coastal Virginia.

As is customary, when we arrived at the site Captain Paul cranked up the VHF radio to the weather channel and its droning computerized voice began babbling in the background. We set anchor, grabbed our masks and associated collecting gear, hopped into the water, and got to work. We were collecting seagrass shoots to measure growth rates, which involved a lot of swimming and diving among our experimental plots in what we affectionately called the ZEN Pole Garden. On about plot number 22, half way through our collections shortly after 3 o’clock in the afternoon, it started. That dreaded cacophony over the VHF radio followed by the ominous blaring of the weather alarm and the warning statement that can mean only one thing – storm!

I never used to be afraid of lightning. I actually found it to be beautiful, exciting even; an awesome display of the raw power of nature ripping the sky above. My sentiments have changed. Continue Reading