A close look at a seagrass creature – caprellids

Students in the UC Davis ZEN class sort specimens of mesograzers – small invertebrates that live in seagrass beds

by Elena Huynh (undergraduate in the UC Davis ZEN class)

My first look under the dissecting microscope at a caprellid amphipod was alarming, to say the least. Enormous Claw-like mouthparts and red eyes stared straight back at me and I jumped back in my seat. Lucky for me, no one was there to observe my visceral reaction to this strange looking animal. After taking a moment, I knew that I would need to get comfortable looking at these odd creatures since we would be performing lots of species identifications during the course of the ZEN class at UCD, so I gave it another look under the scope. Despite the permanent menacing stare, this caprellid was not so scary, albeit a bit bizarre. I noticed a deadly looking spike behind its head and paused before learning that this protuberance is a defining characteristic of this caprellid species—Caprella californica!

After observing this caprellid’s scythe-like claws, I wondered what they were used for. As it turns out, caprellids are pretty clingy. They use their claws (gnathopods) and their legs (pereopods) to hang onto seagrass leaves and algae as they either graze the epiphytes that grow on top of the leaves or filter particles out of the water. Some caprellids can actually help seagrasses grow by cleaning the seagrass leaves and increasing their light exposure, increasing their growth. I guess caprellids would make good housekeepers, since they’re constantly cleaning off dirty surfaces.

Out in the field, I had the opportunity to watch caprellids swim. I wondered how these stick figures managed to get around. Through close observation, I noticed that they do a lot of crawling – which makes sense because they don’t appear to have pronounced flippers or large paddles. When they are not clinging to a surface or crawling they get around by moving like a wave. They curl up their bodies then push their feet and head back at the same time, over and over. It is pretty surprising to see what they manage to do with a body plan I’d consider adverse to swimming.

After doing a little research, I found out that some caprellids have hairs on their antennae – called swimming setae – that help them get around (Caine 1979). Although some can swim, they don’t swim very well nor do they swim for very long. If they’re living in beds of seagrass, all they would really need to be able to do is to hop to get from leaf to leaf. Learning more about what caprellids do for a living has helped me appreciate them, and they just might now be my favorite inhabitants of seagrass beds!

For more information, check out: Caine E.A. Functions of Swimming Setae within Caprellid Amphipods (Crustacea). 1979. Biological Bulletin 156:169-178.

A closer look at an eelgrass inhabitant – the Dungeness crab

by Jason Toy (Undergraduate student in the UCD ZEN class)

Several weeks ago, I was out at Bodega Bay with my classmates from the UCD ZEN course collecting field data for our research projects. As I stood out there in the water in my borrowed waders, I observed quite a few different species of invertebrates as they made their way through the bed of eelgrass. Most were quite familiar to me at that point, but there were a few species, including the Dungeness crab, Cancer magister, that I had not thought of as typical eelgrass inhabitants. I decided to do a little research on the life history of these crustaceans in order to better understand the importance of estuarine seagrass beds to this – and potentially other – important crustacean species.

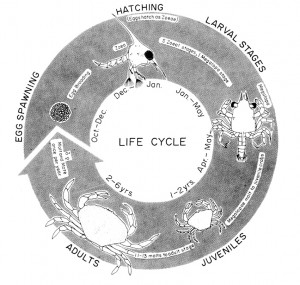

I was surprised to learn that these crabs move around quite a bit during their life histories. Adults mate in nearshore coastal locations in the Pacific Northwest throughout the spring (Pauley et al., 1989), a process in which the male embraces the female for up to 7 days before she molts, after which the actual transfer of sperm occurs. She stores this sperm for about a month until she extrudes her eggs and, in the process of doing so, they are fertilized (Tasto et al., 1893). But her care doesn’t end there. She protects her eggs by storing them on her abdomen for several months until winter (typically December – January). Then one day, these 1-2 million eggs hatch and the baby crabs leave their mother and enter a 105-125 day planktonic larval period. During this time the young Dungeness crab goes through many developmental changes, moving through 5 zoeal and 1 megalopal stages. After reaching the megalopa stage, the young crabs settle out onto the bottoms of bays and estuaries, where they molt into their first juvenile crab stage and begin to actually resemble real crabs.

During field sampling, Jason and classmates found a few juvenile Dungeness crabs hiding amid the eelgrass in Bodega Bay, California

This is where seagrass comes in! Coastal estuaries (like Bodega Harbor) play a critical role for juvenile Dungeness crabs as a nursery. Large numbers of juvenile crabs benefit from the protection and substrate provided by beds of eelgrass (Zostera marina). They cling to and hide within the grass, consuming other small organisms within the habitat (amphipods, isopods, polychaetes, essentially whatever they can catch!) (Pauley et al., 1989). After several molts, subadults and adult Dungeness crabs begin to leave the eelgrass beds and move offshore, but a few do remain in inland coastal waters, hiding among the eelgrass blades.

The role of seagrass beds in the life history of Dungeness crabs is an important interaction to talk about because it is an example of an economic benefit (known as an ecosystem service) provided by seagrass beds. Seagrasses are critical species in coastal environments around the globe, as they form habitat structure and promote a large diversity of organisms. However, like the coral reefs, they are currently in decline due to the effects of human activities. The connection of an economically important species such as Cancer magister to these seagrass ecosystems, however, can help bring attention to this issue, and provide an incentive for the preservation and restoration of this habitat. Help spread the word!

For more information, check out these references:

Pauley, G. B., Armstrong, D. A., Citter, R. V., & Thomas, G. L. (1989). Species Profiles: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Pacific Southwest): Dungeness Crab. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services Biological Report 82(11.121): 7-8.

Tasto, R. N., & Wild, P. W. (1983) Life History, Environment, and Mariculture Studies of the Dungeness Crab, Cancer Magister, With Emphasis on The Central California Fishery Resource. California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 172, 319-320. Retrieved June 11, 2014, from http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt1k4001gs&&doc.view=entire_text

Jason is an aspiring marine ecologist with a passion for all things science. He is a rising senior at UC Davis studying evolution and ecology. His dream job is to be a research SCUBA diver. This summer he will be working in Dr. Jay Stachowicz’s marine ecology lab at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Science boot-camp at the Bodega Marine Lab

by Julie Blaze (UC Davis undergraduate, ZENtern)

Marine biologists don’t often find themselves trekking through dense remote jungles or climbing desolate mountains to conduct their research. Some would say we’ve got it pretty easy – the ocean covers around 70% of the earth’s surface, and studying biodiversity can be as easy as walking out to the coast and digging in the sand. The only downside to the job is that we are captives to the ebb and flow of the tides. My classmates and I in the ZEN class at UCD found that out the hard way when we took a field trip to the Bodega Marine Laboratory to survey the eelgrass growing in Bodega Harbor.

As someone who enjoys sleep, I can honestly say it is difficult to wake up at 5:30 am for any reason. Awake before the sun and trudging across the mud flats before its first rays had even reached the water, I know I wasn’t the only one thinking of the warm, comfy beds we had left behind. My boots were a little too big and kept getting stuck in the mud – I almost went sprawling face down into the mud more than once. As the sun rose, I wondered what we must have looked like to anyone watching from the shore – a zombie-like group of college students floundering in the mud. Slowly we gained more energy and set about surveying a large expanse of the seagrass bed collecting samples and taking measurements. We worked efficiently and conversation picked up as excitement and adrenaline grew with each new discovery and lapping reminder of the incoming tide. At first glance the mudflats and seagrass meadows look barren, but we quickly found that they teemed with life. Critters clung to the grass or buried themselves in the mud – making this eelgrass bed, similar to other seagrass meadows, one of the most diverse ecosystems in the ocean.

After a few hours the water had crept too high for us to work and we headed back to the lab to begin processing our samples. We put in a long day, getting as much done as we could before calling it quits. We all found those cozy beds soon after a late dinner, with the promise of another early field day tomorrow.

The next morning we again rose before the sun and stumbled out into the mud. But this time we were more familiar with the science – the methodology and how to work as a team – and we finished before the water chased us out.

By the end of the weekend I was thoroughly exhausted, but I didn’t care. We had spent an incredible weekend having an amazing adventure. Not only did I learn about the animals and ecosystem we were exploring, but I also learned several things about myself that weekend. First, I learned that I am willing and able to wake up before the sun to do research. Second, not even the wilds of a remote jungle can tempt me away from the mysteries of the ocean. And, finally, one lesson I will never forget – it’s easy to stay awake once your boots flood with freezing cold seawater. But, it’s even easier when you’re also out exploring a location as interesting as a Bodega Bay seagrass bed!

Julie is a graduating senior at UC Davis majoring in Biology. This summer she will be a ZENtern working with Dr. Nessa O’Connor in Ireland. Julie is a true team player and earned the nickname “den mother” during the 3-day, marathon class field trip and subsequent weeks of sample processing back on campus.

Photos contributed by Aaron Goodman.

A test worth taking

by Ellie Marin (UC Davis undergraduate, ZENtern)

Exams are inherently nerve-wracking. First there’s the main concern – did I study enough? Did I study the right material? And then there are other details – I have nightmares about running out of ink in my pen, accidentally missing questions on the back side of an exam

page, or even forgetting to write my name on the top of the exam paper. But, one thing I’d never feared was being stalled by accidently super gluing my hand to the exam paper itself. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from the Seagrass Ecosystem Ecology course taught by Drs. Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz that I’m taking at UC Davis, it’s to be prepared for the unexpected.

Ellie (left) and classmates conduct research at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory for the ZEN undergraduate course in Seagrass Ecosystem Ecology

This hands-on field methods course was designed to educate the undergraduate students participating in the ZEN research (the “ZENterns”) on the methodology, theory, history, and purpose behind seagrass ecology and the Zostera Experimental Network. Our class featured a weekend trip to Bodega Bay, California to conduct field research, student presentations of papers from the primary literature, lectures, and group research activities. Today’s lab practical exam was intended to assess how much we learned from all of the different aspects of the course. In preparation for the exam, I read through my notes. It is a fairly hands-on class, so I wasn’t exactly sure how to study. Chatting with my 11 classmates revealed that we were all in the same boat.

UCD ZEN students perform the class practical exam, which involved answering questions on the course subject matter as well as demonstrating skills developed during the course.

Similar to other laboratory courses, our class practical featured a written portion as well as directed questions from a series of different stations setup around the laboratory. After a timed 30 minutes to complete the 5 pages of short answer questions, I started on the first lab station and the clock ticked down for us to rotate every 5 minutes. Some stations had microscopes with animals under them for us to identify and others materials for us to perform targeted lab skills. I glanced upon the familiar mesograzers under the scope, stumbled through some exotic amphipod identification, measured eelgrass shoots, and even wrote a haiku about epiphytes. The 5 minute periods per station rushed and rushed. I scribbled until the last second. And then I got to one station that fortunately, didn’t involve writing. Yes! Something I’ve done before! “Tether an isopod. Next, tether an amphipod.” We’d done this during our field trip at Bodega Bay to assess predation rates on mesograzers in the field. I got out the glue, set the line, caught the mesograzer. I was all set. No tricks. No doubts. I just had to tether the little guys. But this time it was different.

When we tethered the animals on the field trip, our instructors did not time us. This time I was racing against the clock. I quickly trimmed 20 cm of fishing line for the tether and began tying the proper knots to secure it. It wasn’t this difficult before! This line seems different! The sweat on my hands is not helping! After finally succeeding in tying an appropriate knot, I trimmed the line down and began looking for my first bug. I spotted one and bypass the forceps to plunge my hand into their housing container. I gently grab an isopod and place him on a paper towel to dry off. He’s sedentary. Good news. I grab the glue and squeeze a blob on the knot in my line. The next part is tricky. I have to glue his line – his crustacean leash – right onto his back. Success! After getting it to stick, I put the little guy into a water cup and watch him swim around with his little line in tow.

I’m half done now! I next set my sights on the amphipod. In the heat of the exam, I forget the order of the tethering process and plunge my hand into the container to grab the only amphipod I see. It’s a lively gammarid who undulates all over the paper towel, nearly off the table. This isn’t right! I put him back in the water. Focus! I grab the line and begin to cut to 20 cm again. The knot tying frenzy begins. Just go slow. I make a proper knot and grab the glue. It’s not coming out! I squeeze the glue harder than usual until a thick blob encases my knot… it’ll do. I grab my lively amphipod and he begins twisting and spinning – he’s expected me this time. I use a dropper to drip water on him as he lays on the paper towel. This appears to have a calming effect, and he ceases his tantrum. Now the tricky part. The isopod was big, but this guy is small, just under 1 cm in length. I have to get the glue right on the middle of his back or I risk injuring him. I go for it and miss, somehow getting glue all over my fingers. My fingers start to stick together. I unstick them and attempt to refocus in order to finish out this station – I know I’m almost out of time.

I rearrange my station for better focus, and this involves moving my exam out of the way. Big mistake. I have glued my hand to my exam. I rip the paper off, revealing a thumb and palm covered in ripped, sticky white paper. The timer goes off and I put my amphipod that wouldn’t get tethered back for the next student. “Next Station.” The test continues with new, equally challenging tasks and I proceed, with the paper still glued to my hand

Drs. Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz (left) demonstrate amphipod tethering during the class field trip to the Bodega Marine Lab

The exam was hard. Not because I was underprepared – there are some things in life we can never prepare for. It was not unfair – I had either seen, performed, or learned everything on the exam. It’s not that there wasn’t enough time – everything in life has a time limit. The exam was hard because I have never had so much expected of me in a college class. Our instructors believe that we can do far more than simply answer A, B or C, or regurgitate a paragraph that we memorized from our notes. Our instructors dare us to reveal what we can actually contribute to science. They challenge us to be creative, resourceful, and clever. The point was to experience the exam, not just complete it. Success in research can be measured in how well we perform under stress. Things may not go as planned, but at the root of ecology is evolution, and we must all continue to adapt. This involves accepting our failures, building on our strengths, and focusing on how to move forward.

Some amphipods are meant to be free. Some tests are meant to be stressful. And some hands are meant to be glued.

Ellie is a rising senior at UC Davis pursuing her bachelor’s in biology. Her favorite aspect of the ZEN course was the exposure to field research, and her favorite experiment involved tethering amphipods to test for predation in the Bodega Bay seagrass beds. Her dream job is to be a science communicator and educator. She will be traveling to Ireland and Oregon to assist with ZEN research this summer with Drs. Nessa O’Connor and Fiona Tomas Nash, respectively.

Photos contributed by Aaron Goodman, Pamela Reynolds and Jay Stachowicz.

Surrounded by Science

by Kendra Chan (UC Davis ZEN course undergraduate student)

by Kendra Chan (UC Davis ZEN course undergraduate student)

Over the past school year, I have finally found my people and my calling. I’ve been lucky enough to participate in the UC Davis ZEN course this spring quarter. Unlike your typical research university lecture hall of 300+ students, this class was limited to only 12 undergraduates. But it wasn’t the 6:1 student to faculty ratio that made this class special – rather, it was the people themselves.

As an underclassman, I was herded around the general biology pre-requisite path with the several hundred other students in the college. I found the intro biology series fascinating, but to my dismay, the majority of my peers expressed boredom even in the lab sections. However, this ZEN class was entirely different—it has been one of the few times I’ve been completely surrounded by people that are just as interested in marine ecology as I am, if not more (which I didn’t know was possible). Instead of being held back by classmates that lacked knowledge and interest about the subject at hand (e.g., marine communities), I was motivated and inspired by the passion and expertise demonstrated by the eleven other students and two instructors. Because of this, we were able to progress quickly through lecture topics and have intellectually stimulating discussions.

During the first class period, I knew I had found the right class because we had a lengthy and heated debate about how exactly to deploy the ASUs (Artificial Seagrass Units, or glorified green plastic ribbon) we had just built in order to get the most interesting data. This time, we the students were in control or our own experiment, and we had a plethora of scientifically interesting questions to ask. We weighed the pros and cons of each scenario, and after much discussion settled upon an experimental design.

Needless to say, the past 10 weeks have been a great learning experience for me. Not only did I become well versed in eelgrass ecosystems, but I also learned more about how to be a scientist through lectures, discussion, and my favorite, hands-on field work.

Although I won’t be exclusively working for ZEN this summer, I will still be immersed in eelgrass research. I’m excited to once again be surrounded by marine ecologists in Bodega Bay, and know I will continue to be inspired by both the scientists and the sea.

Kendra Chan is a rising senior at UC Davis. Her favorite experiment in the ZEN class was an assay of predation intensity in Bodega harbor. Her dream is to save the world with science – combining science and education with conservation and sustainability to better understand and utilize natural ecosystems.

Photos contributed by Kendra and Matt Whalen.