Calling all undergrads – get your hands on some science!

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN Coordinator)

Calling all undergraduate students at the College of William and Mary, and surrounding colleges!

The Marine Biodiversity Lab at VIMS has several open positions this fall for research internships in marine ecology, evolution and biodiversity research. Students will receive hands-on research experience involving instruction in both laboratory and field techniques, as well as exposure to cutting-edge research being conducted in the Marine Biodiversity Lab at VIMS.

Research opportunities are in two areas: (1) Ecology of seagrass food webs, as part of the Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN, www.zenscience.org), and (2) Comparative ecology, evolution, and behavior of social shrimps from Caribbean coral reefs.

No experience is necessary, although we encourage applications from detail-oriented students with strong work ethic and communication skills.

Students will be instructed in the use of dissecting microscopes and other tools to identify and quantify local marine flora and fauna of the Chesapeake Bay and other estuaries (ZEN), or of Caribbean invertebrates. Students can expect to gain a strong working knowledge of the scientific process, basic taxonomy and ecological roles of marine organisms, and a greater understanding of fundamental ecological and evolutionary principles. Students will work closely with graduate students, postdoctoral researcher and staff scientists in the Marine Biodiversity Lab (http://www.vims.edu/research/units/labgroups/marine_biodiversity/index.php).

We are recruiting up to 5 students for these volunteer internship positions. Students may earn up to three course credits of MSCI 490 Research in Marine Science.

Students interested in working in this dynamic research environment should e-mail a copy of their resume and unofficial college transcript, with contact information for one WM faculty member who knows you, to both Drs. Pamela Reynolds (reynolds@vims.edu) and Emmett Duffy (jeduffy@vims.edu) to learn more about the position(s). If interested in course credit, contact us ASAP as the add deadline is fast approaching (Sept. 7th!).

The start of something new

by Katelyn Jenkins (College of William and Mary undergraduate)

My name is Katelyn Jenkins and I am a lab technician here at the Marine Biodiversity Lab at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in Gloucester Point, Virginia. This year I will be a junior at the College of William and Mary where I am majoring in biology and minoring in marine science. As a local from Yorktown, Virginia, I have become fascinated with the environmental and economic importance of the world’s largest estuary just down the street – the Chesapeake Bay.

I became involved in research at VIMS during high school in 2008 where I worked in a Marine Conservation and Biology lab. Immediately immersed into field and laboratory work, I knew right away that marine science was a field I wanted to pursue. During 2009-2011 I began working on a research project at William and Mary that aimed to identify and characterize a harmful bacterium recently identified in striped bass in the Chesapeake Bay. Although the topic excited me, it wasn’t until I spent 2 years indoors running multiple PCR’s day after day in the lab that I knew I needed to get back into VIMS where I could study marine science on a much larger scale. In 2011, I began volunteering for Dr. Emmett Duffy in his Marine Biodiversity Lab where I learned to identify various types of seagrass, algae, and LOTS of what we affectionately call ‘bugs’ (small marine invertebrate grazers). Recently I put these new skills to the test when I returned to the lab to work as a technician for the summer.

This summer began on a busy note. I arrived at VIMS the day after I returned from a field course on the Eastern Shore. I had just enough time to unpack before I needed to repack my bags to head to Beaufort, North Carolina with our lab manager Paul Richardson to break down an experiment with the ZEN team at the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS). It was an exciting trip where I had the chance to meet and work with Erik Sotka and his lab group from the College of Charleston in South Carolina in addition to local NC graduate and undergraduate students. My first field experience with this lab group was an exciting one – there is a broad diversity of research projects and techniques employed in the ZEN. One of my favorite parts of the trip was having the chance to stay and work at IMS as well as learn about the ongoing research at this facility, as I have been thinking about potential graduate schools and programs to pursue after graduating from William and Mary.

After returning to VIMS, I have been involved in helping with many projects and picked up new skills: plumbing, sewing, processing chlorophyll samples, taking and sorting biomass cores, and preparing leaf tissue samples for CHN analysis. Although it may seem busy, it has forced me to become mentally organized with all of the different things going on in the lab – something that I think is a very important ‘life skill.’ I have also found that I have gained a lot of confidence in my abilities to recognize what needs to be done, when it needs to be completed by, and what needs to be done to have it completed. There’s a lot more to science than just doing research. I’ve learned that the planning, management and constant juggling of tasks is just as important as actually processing samples.

Melding biology and economics, an undergraduate perspective

by Nicole Rento (undergraduate student at Brown University)

My name is Nicole Rento, and I have been working at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in Gloucester, Virginia with the ZEN team here this summer. I was born and raised in Virginia about 30 minutes away from VIMS in Newport News, where I attended elementary school through high school with fellow lab intern John Schengber. In a weird twist of fate, we both ended up coming home from our first year at different colleges (him at James Madison University and me at Brown University) to work in the Marine Biodiversity Lab. It’s been great working with one of my oldest and best friends, and making new ones here at VIMS.

I just finished my first year at Brown University, and I absolutely love it. I even enjoyed waking up at 6 A.M. most mornings for varsity swim practice, working in the library until late into the night, and especially everything in between. Heading off to college, I was really considering going into the field of medicine. Growing up with two surgeons as parents and listening to their work-related dinner conversations for 18 years, it was hard to imagine doing anything else with my love for biology.

Throughout my first semester at Brown, however, I began to move away from my thoughts of becoming a physician and the idea of having to take two semesters of organic chemistry and towards my love for the environment and ecology. And surprising myself by thoroughly enjoying an introductory economics class during the spring semester, I put myself on the path of double majoring in biology and economics. As to where that will take me, I’m not so sure. At the end of the semester I did know that I wanted to start figuring that out.

My advisor at Brown (Dr. Dov Sax) knows Dr. Duffy and put me in contact with him. I was delighted when he graciously and enthusiastically offered me an internship here in his Marine Biodiversity Lab. So here I am! I started in May, not sure what to expect nor whether I’d be able to see a path to integrate my two passions (biology and economics). I was introduced to the ZEN project on the first day, and have been working on different aspects of the ZEN projects every day since. The ZEN postdoctoral researcher Pamela Reynolds and the lab manager here Paul Richardson started off familiarizing me with the species we would be working with this summer. I learned about the biology and ecology of Zostera, the seagrass around which the ZEN project is formed, and all the animals that live within the habitat it forms including blue crabs, pipe fish, amphipods, gastropods, and isopods, to name a few of my favorites. I never thought I would see so many ‘bugs’ in one summer, let alone count and sort all of them. I’ve gotten pretty speedy at identifying these small invertebrate algae eaters.

I also never thought that I would become so experienced with PVC piping. One of my first tasks was to help Pamela and Paul design the cages for the predator exclusion portion of the project. Another unexpected job: John and I teamed up to make hundreds of plaster blocks for another part of the ZEN project. There were other tasks such as cutting circles of plastic Vexar, and bending hundreds of wires to be placed in the drying plaster blocks. Plaster, PVC piping, Vexar, wires… all for ecology? Yes. Although the connection was hard to find sometimes, as the cages and materials began to take shape, so did my first lesson in ecology: data don’t come out of thin air. First you have to collect those data, and to do that we had to run an experiment. That step came with trips out into the water – field days. I participated in both the set up and breakdown of an experiment to measure the effects of small predators (crabs, shrimp, fish) on seagrass communities. Working under the sun, holding your breath as we worked to secure our cages in murky water, it was no easy task. But seeing those 30 cages, all designed and built by the lab, helping us answer the important questions we ask with this project, was a feeling of incredible accomplishment for me and for my fellow lab members.

After running the experiment there comes countless (often tedious) hours of sample processing. My initial training in identifying seagrass species has come in very handy as we begin examining the final communities from our experimental cages. Finally, after the samples are sorted and the data collected, they have to be analyzed. But we aren’t there yet. I can’t wait to hear the stories from the other sites, and to see what happens as we begin to go through the data from our site’s experiment.

This summer has been a wonderful experience filled with bugs, PVC, great scientists and great friends. Working at VIMS this summer has not only reaffirmed my love for biology, but it has given me insight into the combination of biology with economics. During the summer I heard about other projects that had taken place in our lab and in others. One example was the research our lab did with algae as a biofuel. By running river water through giant flow tanks and back into the river, algae was able to grow on the tanks and remove excess nitrogen and phosphorus from the river water as it ran through the tank, returning cleaner water into the river. The algae could then be harvested and used as a biofuel. Not only is this a breakthrough biologically, but economically as well. In theory, if companies were to install these flow tanks in their factories, they could not only create their own naturally cleaner biofuel, but also help to clean river or lake water. Although still in the preliminary research and development phase, projects like these are beneficial to both the economy and to the environment, and I can definitely see myself being involved in similar projects in the future.

I’m so thankful for having the chance to work with the VIMS Marine Biodiversity Lab this summer. Good luck to the other sites!

Sewing for success

by Caitlin Fikes (VIMS summer 2012 REU student)

Of all the skills I didn’t expect to learn this summer, sewing is definitely top of the list.

As a child, I envied my brothers who were in the Boy Scouts, the American association that teaches young boys and men leadership skills and about the natural world. They got to go hiking and kayaking and learn about animals and the wilderness. I also wanted to make plaster pawprints and carve small wooden boats and learn survival skills, so I decided to try the next best thing, the Girl Scouts. I think my membership in the Girl Scouts lasted for about two months, at most. The boys got to be Bears and Cubs, while we were Brownies and Daisies. And instead of fun skills like archery or campfire-making, in my local troop we were expected to learn cooking and sewing. This was not for me!

It seems ironic that in my pursuit of a historically “masculine” scientific career, I now find myself required to learn what once would have been casually termed a “feminine” skill. Being a scientist, as I recently discovered, also means being a plumber, an engineer, and always a hard worker. Of the many skills needed to construct the equipment for an experiment, here at VIMS sewing is a common requirement. Last week I was taught this skill by a man, our lab manager Paul Richardson, who can sew neater stiches than anyone I know. In science, Paul has remarked, you have to be a Renaissance person with a diverse skillset and an open mind.

What surprised me was not that I had to learn this skill, but that I truly enjoy sewing and apparently have an aptitude for it. After a full day of doing nothing but sewing mesh bags to be used in a field experiment, I was very pleased to see that my lines were getting straighter, and overall I was gaining confidence. I was actually having fun. I reflected that perhaps I should have stayed in Girl Scouts – I might have become a pretty good seamstress by now. Expanding my list of skills is always a good thing, and if not for this summer I might have forever missed out on a skill that I both enjoy and could be good at. Additionally, as a twenty-year-old college student struggling daily to feed myself, I deeply regret not learning how to cook.

Aside from making experimental materials, what other opportunities will I have to use this new needle-and-thread skill? After a quick Google search, I think my next challenge will be to sew my own stuffed animal sea creatures. To the left see one pattern I found online – it looks fairly simple and I firmly believe that you can never own too many cute marine animal paraphernalia.

Fieldwork is never boring

by Serena Donadi (ZEN exchange fellow in Virginia)

One of the most exciting days in the field was when we installed cages for an experiment examining the effects of predators (shrimp, fish, crabs) on the seagrass comminity. After spending many days cutting PVC pipes, sewing meshes and gluing parts together, our cages were finally ready! The plan was to go to the experimental site (Goodwin Islands), pound 60 poles into the sediment and attach our cages to the poles with bungees and cable ties so that the currents wouldn’t drag them away. Plus, to make the cages sink to the sea bottom, we planned to put few shovels of sand inside each mesh.

The cages are basically empty cubes (sides of about 0.5m), made by PVC poles, which are enclosed in a mesh bag. Inside the cages, seagrass communities are recreated by adding mesograzers (gastropods and crustaceans such as amphipods and isopods) and seagrass shoots attached to a plastic screen. The aim of the experiment is to keep all predators (fish and crabs) outside and see what happens… Will the populations of grazers increase? How will such an increase affect the algae and seagrass? Do we see evidence for a trophic cascade, where animals at top trophic levels promote plants at lower trophic levels by controlling species at middle levels?

The weather forecast that day was not very optimistic and there was chance of thunderstorms. We decided to give it a try and started loading everything we need on the boat. The boat was literally full! I wish I’d taken a picture. After adding 10 buckets full of sand, lots of poles, coolers with seagrass and other field. I was really afraid we would sink. But our captain for the day, Kathryn, carefully directed us as to how to load the boat to balance the weight and we were safely on our way. Once we arrived at the field site, the bad weather started rumbling and dark clouds were quickly moving in our direction. I have been in Virginia for more than one month now, but I am still surprised by how fast thunderstorms can appear here and how strong they can be. We decided to quickly head towards a sheltered dock nearby and wait for the storm to pass. After one hour we were back in the field.

It’s odd to say after so many days of terrible heat, but the water was chilly! I was glad I had my wetsuit with me. The sea was still quite rough making the fieldwork quite challenging. To be able to attach the cages to the sea bottom, I wore an incredible heavy weight belt. Despite it, the drift of the waves could still make me roll on the bottom as I snorkeled. The water was so murky that I was not able to see what my hands were doing. Sink to the bottom, stretch my legs to avoid rolling, bind the bungee around the cages and secure everything with cable ties.

After a few hours all of us were trembling because of the cold, the tide was rising, and dark clouds began to cover the sky. Finally the last cage was placed and we jumped on the boat. The sea was stormy and Captain Kathryn did an awesome job in bringing us back to the VIMS boat basin where we store the boats. On our way, heavy rain poured from the sky, hurting on our skin and blinding our eyes. I put on my diving mask and thought how ridiculous I should look wearing a mask and a wetsuit outside of the water. Eventually we arrived at the boat basin, tired, hungry and cold.

That night as I lay in my bed and thought about the day, I realized how lucky I am for having this great chance to work with wonderful people in this amazing ecosystem. It was so much fun! Really, it was one of my favorite days so far in Virginia.

Student profile: REU participant Caitlin

by Caitlin Fikes (VIMS summer 2012 REU student)

Greetings, fellow sea-lovers! My name is Caitlin Fikes, and I’m thrilled to be part of the ZEN family. I am an undergraduate student participating in the National Science Foundation’s REU (research experience for undergraduates) program this summer at VIMS. I’ve been asked how I became involved in the ZEN project and the type of background that makes for a competitive REU applicant. To answer that, let me tell you a little about myself.

I was born in the fine state of Virginia, although for all intents and purposes, this summer was the first time I’ve been here. Growing up my family felt the need to move when the wind changes; we breezed through Virginia and onto another state before I was old enough to remember a thing. I grew up in various states, and developed a love for change and travel and new experiences. I’ve never regretted my vagabond childhood for an instant, and I don’t intend to ever stop moving.

I have always loved nature and wildlife. As a child, I read every book on animals that I could get my hands on, and spent my days traipsing through the woods looking for snakes or deer tracks. But I didn’t know what direction I specifically wanted to go. I loved all nature, all animals, everywhere. When I was fifteen, I acquired my SCUBA certification, and it became very clear to me that I belong in the marine world. I resented the human limitations that required me to eventually come back to the surface for air. I would have remained underwater forever if I could, exploring and observing quite happily. My dream of becoming a marine biologist was born.

Other than obtaining the SCUBA certification itself, I took my first real step towards my dream in 2009, the summer before my senior year of high school. My family was living near Omaha, Nebraska, at the time, and the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha was offering a summer “Eco-Adventure” course. The program consisted of first working with various animals at the Zoo for two weeks, and then culminated in a week-long trip to Cozumel, where the group would be researching coral reefs and snorkeling alongside migrating whale sharks. Barely able to contain my excitement, I applied and was accepted. Caring for a myriad of different animals at the Zoo was extremely informative and fun, but when it came to my marine biology dream, the week in Cozumel sealed the deal for me.

An example of the goby and shrimp pair (courtesy: Operation Pufferfish). To learn more, check out this NY Times page

And it wasn’t just about the charismatic megafauna; the dolphins and whale sharks were fantastic and all, but the highlight of the trip for me was discovering a tiny shrimp/goby pair while diving on the coral reef. I had read about the mutualistic relationship shared by shrimps and gobies, in which the blind shrimp digs a burrow for both to live in and the goby becomes a lookout and bodyguard. I thought it was incredible. To see a pair in the wild was exhilarating. The entire experience felt like a green light to pursue this ambition.

As soon as I returned from Cozumel, I used my connections from the program to obtain a volunteer internship at the Omaha Zoo’s Scott Aquarium. Throughout my entire senior year of high school, I spent every available hour at the aquarium, caring for and learning about the animals there, as well as observing the aquarium’s ongoing research. I learned that the Scott Aquarium was one of the first institutions in the world to successfully raise sexually produced elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) polyps, a very important and highly threatened species of coral. To be so close to the cutting edge of marine biology research was an awesome opportunity; but I was eager to actually jump in and get my feet wet.

I began my college career at the University of Miami in 2010, double majoring in biology and marine science, and double minoring in chemistry and environmental science. Miami has given me a thorough grounding in biology, chemistry, and physics, with emphasis on marine science and exposure to incredible field and research experience probably not available to universities elsewhere. By the end of only two years as an undergrad, I had participated in field studies in coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests. I had helped catch and attach satellite tags to pelagic sharks. I had even started my own research project looking at the effects of a common herbicide on the embryonic development of sea urchins, which I will be continuing in the fall. And, in my spare time, I became certified to assist in rescuing stranded marine mammals.

Throughout this time, I also began to better define my interests and which direction I wish to take in marine biology. I became interested in marine conservation biology, especially in light of the current global fisheries crisis. But even more than that, I am interested in how changes in a particular species can affect the entire ecosystem. What is the nature and strength of the many connections between species? How does tugging one strand shake the food web? And how do the non-biological elements factor into the equation? I realized that what I want to become is actually a marine ecologist.

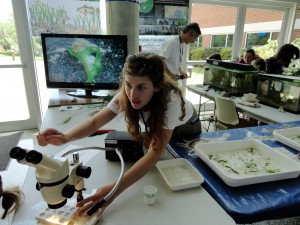

Undergraduates Nicole Rento (left) and Caitlin Fikes (right) prepare materials for a field experiment

Which brings me to this summer. Knowing that I wanted to do research, both to get more experience and to meet the people in my chosen field, I applied to the REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) program here at VIMS. I was surprised and delighted to receive a call from Dr. Pamela Reynolds. When she told me that she felt I was a good fit for the Marine Biodiversity Lab under Dr. Emmett Duffy, I was honored, ecstatic, and extremely nervous!

Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay are gorgeous, VIMS is an incredible institution, and the members of the lab are both great people and great scientists. I would love to be able to follow in the footsteps of the skilled scientists who came before me, and every time we go flying out over the York River to our field sites for another fun day of science and adventure, I can’t help but feel that I’m on the right track.

ZEN at Marine Science Day 2012

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN coordinator)

We introduced the Zostera Experimental Network to the public of Virginia at the tenth annual Marine Science Day (MSD) event at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in May, 2012. Over 2,000 people visited the VIMS campus in Gloucester Point, VA for a full day of behind-the-scenes learning about marine science and the Chesapeake Bay.

Our Marine Biodiversity Lab ran an touch tank exhibit titled “Secretive Seagrass Creatures” where kids and adults had up close encounters with mesograzers and the fish, crabs and shrimp that live in local seagrass habitats. We even hooked up a high definition video camera to one of our microscopes so everyone could watch an amphipod graze on algae and make a mucus tube.

The public was very receptive and inquisitive, especially regarding the ZEN.

Questions we were frequently asked:

Q. What do you mean everyone at the different ZEN field sites did the same experiment?

A. We shipped boxes of experimental materials and sent copies of a detailed protocol (a “how to” guide book), along with instructional videos, to all of the other scientists to ensure that everyone used the same methods. The videos were great as not all of the participating students from the other countries spoke fluent English.

Q. How can you compare the Chesapeake to somewhere like Norway or Alaska? Isn’t it colder up there?

A. Yes, it most definitely is! And this variability, or differences in environmental conditions such as temperature and salinity, is very important. By having a range of environmental conditions, we have more power to understand how these factors such as being in a colder or warmer place can affect the important seagrass communities we are studying.

Q. How do you know these mesograzers are important? They’re really small. Don’t turtles, herbivorous fish and other larger marine animals eat more?

A. Although mesograzers such as amphipods are small, they can eat a lot of algae, especially the algae that grows on the leaves of seagrass and competes with the seagrass for light and nutrients. We have conducted many experiments in tanks and have found that mesograzers can do a good job at keeping the seagrass clean and promoting its growth. While turtles and fish may have larger mouths and take bigger bites of algae, they aren’t necessarily eating the same types of algae or the algae growing on the seagrass, and these larger herbivores aren’t found all over the world. Mesograzers, however, are everywhere and can be very abundant. If you grab a big handful of seagrass in the Chesapeake you can catch hundreds of amphipods!

Q. I live near the Chesapeake. Why should I care about seagrass in Japan or Sweden?

A. By studying other places we can understand how regional and global issues such as pollution, overfishing and seawater warming can threaten our local systems. Oceans make up about 70% of the Earth, and most of them are connected. If we only study the Chesapeake, we loose a valuable opportunity to help understand and predict future challenges.

Our one shortcoming from this year’s Marine Science Day – no one dressed up like an amphipod or other mesograzer for the annual Parade of Marine Life, although while cleaning up our lab we did find a child-sized Idotea (a type of marine isopod) costume from years past. Next time!

ZEN at the 2012 Benthic Ecology Meeting

The Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN) team formally emerged into public view for the first time at the Benthic Ecology Meeting this past week in Norfolk, Virginia. ZEN coordinator Dr. Pamela Reynolds (top center in the photo, in red) presented a first look at the results of our 2011 experiment evaluating the relative importance of grazing, nutrient loading, and abiotic forcing on dynamics of eelgrass (Zostera marina) communities across the Northern Hemisphere.

ZEN had representation from several of our 15 global sites, and a diverse group of PIs, grad students and undergrads, at BEM this year. These included teams from northern Japan (PI Massa Nakaoka and grad student Kyosuke Momota), Quebec (graduate students Julie Lemieux and Laetitia Joseph), Massachusetts (PI James Douglass), North Carolina (PI Erik Sotka, grad students Rachel Gittman and Nicole Kollars, technicians Danielle Abbey and Alyssa Popowich), and Virginia (Emmett Duffy, Pamela Reynolds, Paul Richardson).

The abstract of Pamela’s presentation:

A comparative-experimental approach reveals complex forcing among bottom-up and top-down processes in seagrass communities across the Northern Hemisphere

Pamela L. Reynolds (1); Emmett Duffy (1); Christoffer Boström (2); James Coyer (3); Mathieu Cusson (4); James Douglass (5); Johan Eklöf (6); Aschwin Engelen (7); Klemens Eriksson (3); Stein Fredriksen (8); Lars Gamfeldt (6); Masakazu Hori (9); Kevin Hovel (10); Katrin Iken (11); Per-Olav Moksnes (6); Masahiro Nakaoka (12); Mary O’Connor (13); Jeanine Olsen (3); Paul Richardson (1); Jennifer Ruesink (14); Erik Sotka (15); Jay Stachowicz (16); Jonas Thormar (8)

(1) Virginia Institute of Marine Science, (2) Åbo Akademi University, (3) University of Gronigen, (4) Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, (5) Northeastern University, (6) University of Gothenburg, (7) Universidade do Algarve, (8) University of Oslo, (9) Fisheries Research Agency, Japan, (10) San Diego State University, (11) University of Alaska Fairbanks, (12) Hokkaido University, (13) University of British Columbia, (14) University of Washington, (15) College of Charleston, (16) University of California Davis

Two fundamental challenges to prediction in ecology are complexity and idiosyncrasy. How do we evaluate the importance and generality of multiple, interacting factors in mediating ecological structure and processes? One promising way forward is the comparative-experimental approach, integrating standardized experiments with observational data. In summer 2011 the Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN), a collaboration among ecologists across 15 Northern Hemisphere sites, initiated parallel field experiments exploring bottom-up and top-down control in eelgrass (Zostera marina) communities. Eelgrass is among the most widespread marine plants, forming ecologically and economically important but threatened coastal habitats. We factorially added nutrients and excluded small crustaceans (mesograzers) using a degradable chemical deterrent for four weeks, and measured responses of associated plant and animal communities. As expected, results varied strongly across the global range. Our cage-free deterrent strongly reduced crustacean grazers; at several sites grazer exclusion released blooms of epiphytic algae and/or sessile invertebrates. In Chesapeake Bay, these blooms reduced eelgrass biomass after eight weeks, demonstrating mutualistic dependence between eelgrass and mesograzers. Surprisingly, nutrient addition had little effect on epiphytes, except in Massachusetts and Sweden where grazers are suppressed by mesopredators. Ongoing research is analyzing the relative influence of grazer diversity and environmental forcing in mediating these processes.

Analysis of the 2011 experiments is still under way–even as we swing into high gear for planning the 2012 experiment. We will be presenting the complete results of the 2011 experiment at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland (August 2012) and the 47th European Marine Biology Symposium in Arendal, Norway (September 2012). We hope to see you at one or another of these events!

A summer of adventure

By Akela Kuwahara, VIMS REU student summer 2011 (Humboldt State University)

Last week I earned my Invertebrate Zoology team at Humboldt State University 10 extra credit points for successfully identifying a gammaridean and caprellid amphipod, a mysid shrimp, and several Palmonetesshrimps! How, you ask? One word: ZEN.

This past summer I was in the REU program at VIMS working with Dr. Duffy’s Marine Biodiversity Lab. The ZEN project had just begun when I arrived in Virginia and I quickly set to work making experimental equipment and processing seagrass samples. Coastal Virginia looks nothing like the rocky California Coast where I currently go to school at Humboldt State University, nor like where I grew up on the Big Island of Hawaii.

I have had few experiences as enriching, educational, and career-focusing as my internship with the VIMS ZEN team. I had an up-close encounter with a juvenile terrapin who tried to nest in my hair, and an encounter with a sea nettle that wrapped my leg in a less than tender embrace. I became an expert at pouring cups of wet plaster, identifying a severed head or lone backside of the tiny amphipod Gammarus mucronatus, distinguishing between seagrasses Ruppia and Zostera, doing the sting-ray-shuffle, writing international UPS labels in the nick of time, and so much more.

Sadly, since my time at VIMS has ended, these skills have been poorly utilized. They have, however, given me a better understanding of marine ecology and the functioning of seagrass habitats, and they’ve earned me 10 extra credit points in Invertebrate Zoology! Emmett Duffy’s lab at VIMS is a craftily chosen group of people who have collectively helped to steer my interest in graduate studies towards subtidal ecosystems and their global presence and impact. I can’t wait to hear about where the ZEN is headed, and the progress that it has made. It was a summer well spent.

Photos by JE Duffy, PL Reynolds, JP Richardson

This is science?

By Kara Gadeken, College of William & Mary undergraduate student

Undergraduate student Kara Gadeken takes water salinity measurements at Goodwin Islands, Virginia USA

Interning at VIMS during the hectic months when the ZEN project was at its peak was an experience that I will never forget.

The main reason that I wanted to take part in it was that, as an impassioned yet inexperienced college student, I had a reasonable knowledge base in biology but had no idea what it was like to actually do research, much less to be a part of such a grand-scale project as the ZEN. I approached Dr. Duffy at the suggestion of one of my professors at William and Mary, and luckily enough at this point his lab could use all of the help I could give.

I think the first thing that I realized while working in the Marine Biodiversity lab was that an insane amount of planning and preparation goes into research. Pamela had sticky notes and checklists and reminders all over everything in the lab, and two weeks of putting supplies together could count on one efficient day in the field. I also discovered that biologists, and especially experimental ecologists, almost have to have some engineering blood in them. In my first week at VIMS I sat in on a lab meeting to figure out how to design and construct cages to exclude predatory fish and crabs out in the seagrass beds. Time after time I heard, “How about this random thing? Hmm, I’m not sure that’ll work…How about this other random thing? Yeah, we can make something out of that!” Someone would hold up a piece of bent wire, some cable ties, bits of rope and mesh, some plastic plates. They hurled out idea after idea, trying to come up with something that could be constructed into a cage-like apparatus that would anchor into the sediment and withstand the waves. I remember stitching mesh together on an industrial sewing machine thinking, “This is science?” It didn’t take me long to realize that experiments are complicated. Not everything is perfect, and sometimes you have to work with what you’ve got, or make something new. Continue Reading