Science – it’s electric!

By Pamela Reynolds (VIMS; ZEN Coordinator) with contributions from Paul Richardson and Akela Kuwahara

There are few times in my life that I can honestly say that I was terrified. Feeling the Loma Prieta earthquake in ’89, (nearly) tripping over a cottonmouth snake, taking my qualifying exams all stand out. So does the 28th of June in 2011.

It started out as a normal day, or at least as normal as a day of fieldwork can go at the ZEN site in Virginia. It began with the usual flurry of activity in the early morning packing the experimental equipment and loading the boat, checking the associated weather websites and filling out the float plan, slathering on sunscreen and pulling on life jackets and dive booties. It was a typical hot, humid, and sunny summer field day in coastal Virginia.

As is customary, when we arrived at the site Captain Paul cranked up the VHF radio to the weather channel and its droning computerized voice began babbling in the background. We set anchor, grabbed our masks and associated collecting gear, hopped into the water, and got to work. We were collecting seagrass shoots to measure growth rates, which involved a lot of swimming and diving among our experimental plots in what we affectionately called the ZEN Pole Garden. On about plot number 22, half way through our collections shortly after 3 o’clock in the afternoon, it started. That dreaded cacophony over the VHF radio followed by the ominous blaring of the weather alarm and the warning statement that can mean only one thing – storm!

I never used to be afraid of lightning. I actually found it to be beautiful, exciting even; an awesome display of the raw power of nature ripping the sky above. My sentiments have changed. Eyes wide searching the horizon, we noticed some puffy clouds in the distance. But they were still far away, a barely visible smudge on the horizon. Captain Paul swam back to the boat and called the VIMS marine safety office for an update. Where was the storm? Should we head back? That morning the forecast had said 20% chance of rain. Would we miss it? The VHF radio blared again. “Thunderstorm warning for Williamsburg, York, Gloucester…” We grabbed our gear and made double time back to the boat and packed up. That benign smudge on the horizon was beginning to look a bit more ominous.

Over the droning of the VHF I could hear our marine safety officer’s voice on the other end of the phone say “You need to get your <fill in the explicative> home!” Paul hung up and started up the engine and we all held on tight. Cumulonimbus heads suddenly rose from the north and we began to see a line of haze that corresponded to rain. The storm was up across the river and heading toward us. Time to go home.

I wish we had photos, but we were too busy trying to save our <explicative>. The storm blew in with furious force and the ride home was simultaneously amazing and beautiful, but we knew, potentially deadly. A descending dark gray ceiling of clouds bristling with electrical charge bathed the river in a light rarely seen. We zoomed up the York River in the research vessel Teal, crouched as low as possible, hands over head and ears to avoid the pounding rain buffeted by the wind, and we crossed our fingers that the next bolt of lightening missed. Being the highest point around, soaking wet, with a stainless steel steering wheel in his hands was not Paul’s idea of a good way to get a charge out of life. Nor mine. Paul put the hammer down and blasted home as fast and safely as our 150 hp Yamaha would push us.

We arrived just in time. The Teal slid into her berth and someone shouted “Line!” and someone else “Quick!” and then, “Save the samples!”

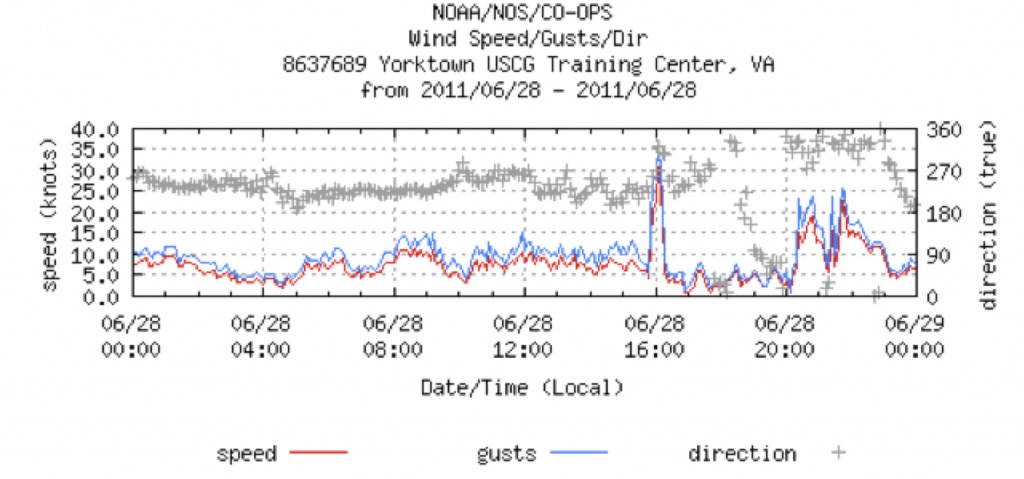

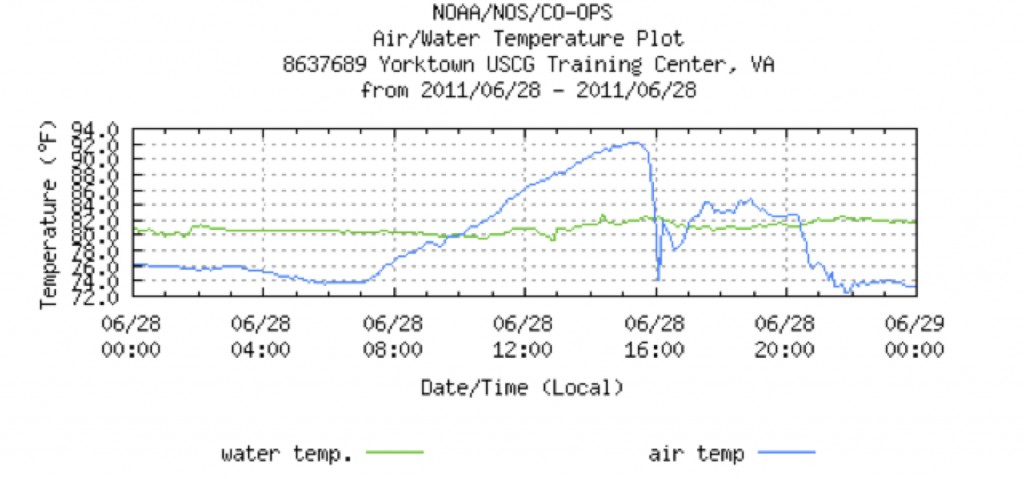

In retrospect this may sound crazy, but after a long summer of fieldwork each small plastic bag, every tiny vial of specimens from the field is as precious as the rarest gem. Mindful to duck with each thunder crack and to remove the boat pugs so the rain didn’t sink the Teal, we tied off and scrambled up the dock with the cooler full of samples and dashed into the relative safety of the vessels office trailer. Ping-pong sized hail pummeled the trailer’s windows, 36 knot gusts of wind ripped into awnings, tin roofs crackled and crinkled above, the power flickered and died. We stood shivering in our wetsuits and life jackets amid growing puddles of water on the trailer floor. Five long minutes and the lights were back on. The clouds had trailed off into the distance. The sun, shining down more brightly than ever before, belied the storm’s existence. But all about were spreading puddles and a fresh, clean crispness to the air.

I was reminded by something my friends from North Carolina told me before I moved out East and started graduate school – if you don’t like the weather in the South, wait a few minutes and it will change. Especially in the summer time, where it seems like every afternoon has a 30% chance of thunderstorms which, when they do occur, pop up quickly and fiercely. Normally we think about racing to complete our fieldwork before the tide rises above our necks, but here we also have to move swiftly just in case those pretty, puffy white clouds on the horizon turn on us. No amount of scouring NOAA weather websites for the day’s forecast can entirely prepare you for being caught in a storm out on the marsh. But quick thinking in the field and good communication among the team makes sure everyone gets home safe, and with a cooler full of samples. Now, who wants to sort some seagrass?

Photos by JE Duffy, PL Reynolds; Figures from NOAA.

Comments are closed.