Melding biology and economics, an undergraduate perspective

by Nicole Rento (undergraduate student at Brown University)

My name is Nicole Rento, and I have been working at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in Gloucester, Virginia with the ZEN team here this summer. I was born and raised in Virginia about 30 minutes away from VIMS in Newport News, where I attended elementary school through high school with fellow lab intern John Schengber. In a weird twist of fate, we both ended up coming home from our first year at different colleges (him at James Madison University and me at Brown University) to work in the Marine Biodiversity Lab. It’s been great working with one of my oldest and best friends, and making new ones here at VIMS.

I just finished my first year at Brown University, and I absolutely love it. I even enjoyed waking up at 6 A.M. most mornings for varsity swim practice, working in the library until late into the night, and especially everything in between. Heading off to college, I was really considering going into the field of medicine. Growing up with two surgeons as parents and listening to their work-related dinner conversations for 18 years, it was hard to imagine doing anything else with my love for biology.

Throughout my first semester at Brown, however, I began to move away from my thoughts of becoming a physician and the idea of having to take two semesters of organic chemistry and towards my love for the environment and ecology. And surprising myself by thoroughly enjoying an introductory economics class during the spring semester, I put myself on the path of double majoring in biology and economics. As to where that will take me, I’m not so sure. At the end of the semester I did know that I wanted to start figuring that out.

My advisor at Brown (Dr. Dov Sax) knows Dr. Duffy and put me in contact with him. I was delighted when he graciously and enthusiastically offered me an internship here in his Marine Biodiversity Lab. So here I am! I started in May, not sure what to expect nor whether I’d be able to see a path to integrate my two passions (biology and economics). I was introduced to the ZEN project on the first day, and have been working on different aspects of the ZEN projects every day since. The ZEN postdoctoral researcher Pamela Reynolds and the lab manager here Paul Richardson started off familiarizing me with the species we would be working with this summer. I learned about the biology and ecology of Zostera, the seagrass around which the ZEN project is formed, and all the animals that live within the habitat it forms including blue crabs, pipe fish, amphipods, gastropods, and isopods, to name a few of my favorites. I never thought I would see so many ‘bugs’ in one summer, let alone count and sort all of them. I’ve gotten pretty speedy at identifying these small invertebrate algae eaters.

I also never thought that I would become so experienced with PVC piping. One of my first tasks was to help Pamela and Paul design the cages for the predator exclusion portion of the project. Another unexpected job: John and I teamed up to make hundreds of plaster blocks for another part of the ZEN project. There were other tasks such as cutting circles of plastic Vexar, and bending hundreds of wires to be placed in the drying plaster blocks. Plaster, PVC piping, Vexar, wires… all for ecology? Yes. Although the connection was hard to find sometimes, as the cages and materials began to take shape, so did my first lesson in ecology: data don’t come out of thin air. First you have to collect those data, and to do that we had to run an experiment. That step came with trips out into the water – field days. I participated in both the set up and breakdown of an experiment to measure the effects of small predators (crabs, shrimp, fish) on seagrass communities. Working under the sun, holding your breath as we worked to secure our cages in murky water, it was no easy task. But seeing those 30 cages, all designed and built by the lab, helping us answer the important questions we ask with this project, was a feeling of incredible accomplishment for me and for my fellow lab members.

After running the experiment there comes countless (often tedious) hours of sample processing. My initial training in identifying seagrass species has come in very handy as we begin examining the final communities from our experimental cages. Finally, after the samples are sorted and the data collected, they have to be analyzed. But we aren’t there yet. I can’t wait to hear the stories from the other sites, and to see what happens as we begin to go through the data from our site’s experiment.

This summer has been a wonderful experience filled with bugs, PVC, great scientists and great friends. Working at VIMS this summer has not only reaffirmed my love for biology, but it has given me insight into the combination of biology with economics. During the summer I heard about other projects that had taken place in our lab and in others. One example was the research our lab did with algae as a biofuel. By running river water through giant flow tanks and back into the river, algae was able to grow on the tanks and remove excess nitrogen and phosphorus from the river water as it ran through the tank, returning cleaner water into the river. The algae could then be harvested and used as a biofuel. Not only is this a breakthrough biologically, but economically as well. In theory, if companies were to install these flow tanks in their factories, they could not only create their own naturally cleaner biofuel, but also help to clean river or lake water. Although still in the preliminary research and development phase, projects like these are beneficial to both the economy and to the environment, and I can definitely see myself being involved in similar projects in the future.

I’m so thankful for having the chance to work with the VIMS Marine Biodiversity Lab this summer. Good luck to the other sites!

Interest in the ‘ecological organism’ leads student to pursue “wet” science

by Stephanie Cimon (graduate student at the ZEN site in Quebec, Canada)

My name is Stephanie. I was born 25 years ago in Saint-Nicéphore (Québec, Canada). I am a Master’s student at the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi. Even two years ago, I had no idea I wanted to become a marine biologist. I always wanted to work with living things, from big animals to tiny cells. When it was time to choose a university program, I was captivated by how the human body works. So, I did my bachelor’s in biomedical sciences in Montreal. I was really interested in this subject, but while finishing my degree I realized that I wanted to spend time outside and so I started to take ecology courses. I think an ecosystem works a little bit like an organism. My curiosity in how the human body works was replaced by a interest in how entire ecosystems work. I then started another bachelor’s degree in biology at Chicoutimi and realized that I wanted to work with something related to water. I’ve always loved the water and especially the seaside.

In the winter of 2011, we had to choose a project for a course called “Introduction to Research”. I visited Dr. Mathieu Cusson who introduced me to the ZEN project. I knew I wanted to be part of it. Last summer I was hired to work in the intertidal zone of the St-Lawrence Estuary for the ZEN experiment and for three other projects. I spent all summer moving from one place to another and I really enjoyed it. Mathieu was really busy, and so I had to organize the planning of our ZEN experiment and prepare for the fieldwork and laboratory processing at our site. Thank to Drs. Cusson, Duffy and Reynolds, everything went well and I appreciated the experience I acquired doing it.

Our site is situated in Pointe-Lebel (N 49°06’, W 68°10’). The water there is quite cold at 13°C (55°F). There are some “holes” in the intertidal due to scouring action by ice. The holes can be more than 30 cm deeper than the surrounding area. We didn’t have wetsuits and instead used waders, so we had to watch our steps so we wouldn’t fall into one of those holes. The third day we were there to start the experiment, one of our team took the unwanted plunge. Fortunately that day, the tide was so low that the water was “hot” at 20°C (68°F). A few times, some of us made the mistake of bending a little bit too much while working in the water and flooded the waders with the icy seawater. I did it once, and by the end of that day the only part of my body that was not wet was my head. It’s a bit of a game to see who can stay the driest, or manages to get the wettest! Fieldwork is always good entertainment.

To carry the experimental materials out to our field site, we used beach boats, but every once and a while something would fall into the water. For example, somehow Mathieu’s backpack slid off the boat and onto the water where it rolled for few seconds before I grabbed it. When working in the field anything valuable needs to be kept in water tight bags to be safe.

This year, we are still participating in ZEN, but because we do not have enough time and labor, we were only able to participate in one of the projects involving assessing the intensity of predation of small crabs, shrimp and fish on small invertebrate grazers at our site. Our first visit to the site in June was a complete fiasco! We had such bad weather that we lost all of the experimental materials. First, a storm took our five minnow traps. We didn’t want to believe it, so we searched an hour. We kept up hope because the visibility in the water wasn’t good. After recovering two of the five bricks used to attach the traps, we had to face the truth. The ropes did not make it. We also lost 88 podsicles (a special little pole where a food item is glued) out of the 96 we deployed. We were luckier on our next visit last week. We had beautiful sun and hot weather. We recovered everything. We felt like it was a holiday!

I am now starting the fieldwork for my master’s degree studying the rocky shore of the St-Lawrence Estuary. My project is about the resilience (ability of a system to recover quickly) of the local benthic community. We removed everything living in 50×50 cm quadrats and burned the rock to be sure all we had left was bare rock. I want to examine the succession (development over time) of the algae and whether different perturbations such as grazing, nutrient enrichment, or thermal stress (through the removal of canopy forming fucales algae) can influence the ability of the community to recover. I think the algae will grow faster with nutrient enrichment, and that the grazer removals will cause slower recovery to pre-experimental conditions as grazing may be important for algal succession. I expect that thermal stress by canopy removal will make the return to normal difficult. I am excited to see if there are some differences. For now, there is still almost nothing on the rock, but I expect to soon see some mussels and algae begin colonizing the area.

Marine ecology is a stimulating profession I am pleased to discover day after day. I am glad to participate to the ZEN project for the second year and I am looking forward to see the results. It helped me choose my path as a biologist. Thank you ZEN!

First week in Akkeshi, Japan

by Nicole Kollars (ZEN graduate student fellow in Northen Japan)

I do not think my wetsuit had a chance to fully dry out this week as we were in the water at the ZEN field site everyday. With several experimental pushes (setting up an experiment to measure predator impacts on mesograzers, maintaining the main ZEN experiment, and surveys of the ambient predator community) it was a busy week for eelgrass science in northern Japan!

Science by canoe

A team of four made maintaining the ZEN experimental plots a smooth and efficient process. We used a canoe to keep bags of plaster blocks, extra cable-ties, and spare scissors easily accessible. While one person paddled around the plots and handed out supplies, the rest of us used mask and snorkel to change the old blocks out for the new. Luckily, the tide was at a good height to make snorkeling easy but the ever-present jellies still makes working at this site quite challenging!

Learning how to catch a fish

Before traveling to Japan I had never appreciated how creatively scientists can modify their use of the same or similar experimental gear to overcome obstacles posed by working under diverse field conditions. I’ve surveyed small aquatic predators before using a seine net (a large net attached to two poles dragged through the seagrass to capture fish and other predators). But, I had never seen one used quite like they do at the ZEN site in Akkeshi. We used a typical seine design (floats on top, weighted on the bottom), but with the addition of a tow net attached to one side of the seine. In the water, the seine net was walked out until completely stretched in one direction. Then we walked the ends of the net toward each other to form an enclosed circle. Moving very slowly, we gradually decreased the circle in size until all the fish were forced into the tow net. The tow net could then be emptied into a bucket and the fish counted, measured, and released. It was an effective design that did not require spending time picking the fish out of the netting of a traditional seine. I think this purse seining technique is similar to techniques that shrimpers and other commercial fishermen use to capture fish in the open ocean, but it’s not something I’d ever seen before. But that’s part of why I’m in Japan – to learn new techniques and do rigorous science at the same time.

A surprise trip to a tidal flat

To my absolute delight, after finishing work at the ZEN site one morning we swung by a tidal flat where I could collect samples of the local Gracilaria seaweed for my thesis research. While this species is introduced and invasive in the Southeastern USA, it is native to mudflats here in Akkeshi. The shallow water prevented the boat from getting too close to the shore, so we had to hike over one kilometer in shin-deep mud before we started seeing the seaweed. This happened to be the day when the sun shone bright and my 10 mm worth of neoprene grew unbearable as I made my way through the mud. But the end result of seeing Gracilaria in its native habitat was well worth the exertion and I was able to collect enough samples for my project and make some useful observations.

Interestingly, in the Akkeshi mudflats most of the Gracilaria is settled onto the shells of a local gastropod. This contrasts to the Southeastern USA where the decorator polychaete Diopatra attaches fragments of Gracilaria to its tube. In both cases, the seaweed is using an animal for substrate but through very different mechanisms. I also found amphipods living on Gracilaria. Similar to how the amphipods in the eelgrass beds are larger in Akkeshi than in the Carolinas, the amphipods I found on Gracilaria are gigantic compared to what I have seen in Charleston. A huge thanks goes out to Dr. Nakaoka for facilitating the endeavor, Dr. Honda and Kyosuke-san for hiking through the mud and collecting samples with me, and ZEN for bringing me to Japan!

All in a week’s work

Now at the week’s end my wetsuit finally has a chance to dry out and I look forward to a weekend of rest, a lab dinner party (with the promise of local Hokkaido seafood and good sake), and a canoeing trip up the Bekanbeushi River. “Work hard, play hard” definitely describes the life of a marine field ecologist here in Japan. Otsukaresama (thank you for your hard work) ZEN team!

Fieldwork is never boring

by Serena Donadi (ZEN exchange fellow in Virginia)

One of the most exciting days in the field was when we installed cages for an experiment examining the effects of predators (shrimp, fish, crabs) on the seagrass comminity. After spending many days cutting PVC pipes, sewing meshes and gluing parts together, our cages were finally ready! The plan was to go to the experimental site (Goodwin Islands), pound 60 poles into the sediment and attach our cages to the poles with bungees and cable ties so that the currents wouldn’t drag them away. Plus, to make the cages sink to the sea bottom, we planned to put few shovels of sand inside each mesh.

The cages are basically empty cubes (sides of about 0.5m), made by PVC poles, which are enclosed in a mesh bag. Inside the cages, seagrass communities are recreated by adding mesograzers (gastropods and crustaceans such as amphipods and isopods) and seagrass shoots attached to a plastic screen. The aim of the experiment is to keep all predators (fish and crabs) outside and see what happens… Will the populations of grazers increase? How will such an increase affect the algae and seagrass? Do we see evidence for a trophic cascade, where animals at top trophic levels promote plants at lower trophic levels by controlling species at middle levels?

The weather forecast that day was not very optimistic and there was chance of thunderstorms. We decided to give it a try and started loading everything we need on the boat. The boat was literally full! I wish I’d taken a picture. After adding 10 buckets full of sand, lots of poles, coolers with seagrass and other field. I was really afraid we would sink. But our captain for the day, Kathryn, carefully directed us as to how to load the boat to balance the weight and we were safely on our way. Once we arrived at the field site, the bad weather started rumbling and dark clouds were quickly moving in our direction. I have been in Virginia for more than one month now, but I am still surprised by how fast thunderstorms can appear here and how strong they can be. We decided to quickly head towards a sheltered dock nearby and wait for the storm to pass. After one hour we were back in the field.

It’s odd to say after so many days of terrible heat, but the water was chilly! I was glad I had my wetsuit with me. The sea was still quite rough making the fieldwork quite challenging. To be able to attach the cages to the sea bottom, I wore an incredible heavy weight belt. Despite it, the drift of the waves could still make me roll on the bottom as I snorkeled. The water was so murky that I was not able to see what my hands were doing. Sink to the bottom, stretch my legs to avoid rolling, bind the bungee around the cages and secure everything with cable ties.

After a few hours all of us were trembling because of the cold, the tide was rising, and dark clouds began to cover the sky. Finally the last cage was placed and we jumped on the boat. The sea was stormy and Captain Kathryn did an awesome job in bringing us back to the VIMS boat basin where we store the boats. On our way, heavy rain poured from the sky, hurting on our skin and blinding our eyes. I put on my diving mask and thought how ridiculous I should look wearing a mask and a wetsuit outside of the water. Eventually we arrived at the boat basin, tired, hungry and cold.

That night as I lay in my bed and thought about the day, I realized how lucky I am for having this great chance to work with wonderful people in this amazing ecosystem. It was so much fun! Really, it was one of my favorite days so far in Virginia.

Student profile: REU participant Caitlin

by Caitlin Fikes (VIMS summer 2012 REU student)

Greetings, fellow sea-lovers! My name is Caitlin Fikes, and I’m thrilled to be part of the ZEN family. I am an undergraduate student participating in the National Science Foundation’s REU (research experience for undergraduates) program this summer at VIMS. I’ve been asked how I became involved in the ZEN project and the type of background that makes for a competitive REU applicant. To answer that, let me tell you a little about myself.

I was born in the fine state of Virginia, although for all intents and purposes, this summer was the first time I’ve been here. Growing up my family felt the need to move when the wind changes; we breezed through Virginia and onto another state before I was old enough to remember a thing. I grew up in various states, and developed a love for change and travel and new experiences. I’ve never regretted my vagabond childhood for an instant, and I don’t intend to ever stop moving.

I have always loved nature and wildlife. As a child, I read every book on animals that I could get my hands on, and spent my days traipsing through the woods looking for snakes or deer tracks. But I didn’t know what direction I specifically wanted to go. I loved all nature, all animals, everywhere. When I was fifteen, I acquired my SCUBA certification, and it became very clear to me that I belong in the marine world. I resented the human limitations that required me to eventually come back to the surface for air. I would have remained underwater forever if I could, exploring and observing quite happily. My dream of becoming a marine biologist was born.

Other than obtaining the SCUBA certification itself, I took my first real step towards my dream in 2009, the summer before my senior year of high school. My family was living near Omaha, Nebraska, at the time, and the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha was offering a summer “Eco-Adventure” course. The program consisted of first working with various animals at the Zoo for two weeks, and then culminated in a week-long trip to Cozumel, where the group would be researching coral reefs and snorkeling alongside migrating whale sharks. Barely able to contain my excitement, I applied and was accepted. Caring for a myriad of different animals at the Zoo was extremely informative and fun, but when it came to my marine biology dream, the week in Cozumel sealed the deal for me.

An example of the goby and shrimp pair (courtesy: Operation Pufferfish). To learn more, check out this NY Times page

And it wasn’t just about the charismatic megafauna; the dolphins and whale sharks were fantastic and all, but the highlight of the trip for me was discovering a tiny shrimp/goby pair while diving on the coral reef. I had read about the mutualistic relationship shared by shrimps and gobies, in which the blind shrimp digs a burrow for both to live in and the goby becomes a lookout and bodyguard. I thought it was incredible. To see a pair in the wild was exhilarating. The entire experience felt like a green light to pursue this ambition.

As soon as I returned from Cozumel, I used my connections from the program to obtain a volunteer internship at the Omaha Zoo’s Scott Aquarium. Throughout my entire senior year of high school, I spent every available hour at the aquarium, caring for and learning about the animals there, as well as observing the aquarium’s ongoing research. I learned that the Scott Aquarium was one of the first institutions in the world to successfully raise sexually produced elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) polyps, a very important and highly threatened species of coral. To be so close to the cutting edge of marine biology research was an awesome opportunity; but I was eager to actually jump in and get my feet wet.

I began my college career at the University of Miami in 2010, double majoring in biology and marine science, and double minoring in chemistry and environmental science. Miami has given me a thorough grounding in biology, chemistry, and physics, with emphasis on marine science and exposure to incredible field and research experience probably not available to universities elsewhere. By the end of only two years as an undergrad, I had participated in field studies in coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests. I had helped catch and attach satellite tags to pelagic sharks. I had even started my own research project looking at the effects of a common herbicide on the embryonic development of sea urchins, which I will be continuing in the fall. And, in my spare time, I became certified to assist in rescuing stranded marine mammals.

Throughout this time, I also began to better define my interests and which direction I wish to take in marine biology. I became interested in marine conservation biology, especially in light of the current global fisheries crisis. But even more than that, I am interested in how changes in a particular species can affect the entire ecosystem. What is the nature and strength of the many connections between species? How does tugging one strand shake the food web? And how do the non-biological elements factor into the equation? I realized that what I want to become is actually a marine ecologist.

Undergraduates Nicole Rento (left) and Caitlin Fikes (right) prepare materials for a field experiment

Which brings me to this summer. Knowing that I wanted to do research, both to get more experience and to meet the people in my chosen field, I applied to the REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) program here at VIMS. I was surprised and delighted to receive a call from Dr. Pamela Reynolds. When she told me that she felt I was a good fit for the Marine Biodiversity Lab under Dr. Emmett Duffy, I was honored, ecstatic, and extremely nervous!

Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay are gorgeous, VIMS is an incredible institution, and the members of the lab are both great people and great scientists. I would love to be able to follow in the footsteps of the skilled scientists who came before me, and every time we go flying out over the York River to our field sites for another fun day of science and adventure, I can’t help but feel that I’m on the right track.

An excellent day in the field

by Max Overstrom-Coleman (ZEN exchange fellow) on July 10, 2012

To be honest it is actually the 11th, but as I sit up writing this at just a shade past midnight, time seems more irrelevant than ever. I am still feeling energized from the tremendous amount of work James Douglass, my host site mentor here in Massachusetts, and I accomplished. Today we completed the sampling for the main ZEN experiment at our site. It is days like today that reinforce my love for field-work and marine science.

As I drove onto Nahant this morning the tide was halfway through its ebb and I was mentally going over the plan for what was sure to be a long day. As we envisioned it we would be in the water by about 0900 (the low was at about 1100) and our list of objectives was ambitious:

- Sample mesograzers (collect samples underwater from each experimental plot using standardized grab bags)

- Collect 10 eelgrass shoots per plot for three different analyses (1 for an analysis of epiphyte loading that would have to be done that night)

- Sample the percentage cover and canopy height of eelgrass in each plot

- Collect all of the experimental materials (bags of nutrients, plaster, and seagrass litter) to assess treatment loading and eelgrass decomposition

At this point in the season James and I are getting into a rhythm with each other. I feel like we are becoming a good team, and our ambitious plan seemed completely reasonable.

With the Northeastern Marine Lab dive truck loaded up with coolers, kayaks, dive gear and sampling equipment, we arrived at the site at a perfect tide height. The cove was empty except for a small family splashing in the shallows. It turned out that, as usual, when people show up in SCUBA gear, kids in the 8-12 age group lose their minds. I know I used to, that’s why I got certified the day I turned 13 (that was 20 years ago next week – wow I’m getting old!) and volunteered as a research diver the summer I turned 16.

It was immediately obvious that we were suddenly celebrities and it was a great opportunity to explain what we were doing and why, both to the parents and children. I think it is extremely important to communicate with the public about our research; they have to understand why it is important and see our passion. How else can we expect them to fund the science we consider so essential? In reflection, that interaction may have been one of the most important things I did today.

The sun was cooking up a hot day and it did not disappoint – I made serious strides on my raccoon tan. Before too long we were overheating and had to get in the water. I’ll spare you the nitty-gritty details, but to those of you out there who have spent that kind of time on and in the water, diving, sampling, and executing a scientific plan, I tell you honestly, it went totally smooth. By the end of it we were pretty spent and plenty hot, and it felt long but we did it without any of the usual snafus – dropped / lost / forgotten / broken gear, adverse conditions, etc… What I call an excellent day in the field.

With coolers loaded to the brim, we made it back to the lab just as we were crashing from lack of food. But after a thorough wash down to scrub off all the mud and sand that gets everywhere, and a hasty bite of food, we were back at it, preparing samples for preservation and immediately processing others. As the sunset bathed a few straggling clouds in a range of oranges and purples we were engrossed in scraping and filtering epiphytes for chlorophyll analysis, feeling pretty proud of all we accomplished. Just another day in the life of a marine ecologist.

Ducking and dodging thunderstorms in Virginia

by Kathryn Sobocinski (VIMS graduate student)

I’m a PhD student at VIMS, co-advised by Drs. Emmett Duffy and Rob Latour. While my contributions to the ZEN project thus far have been minimal as I’m in the midst of writing up my dissertation research, I did get drafted into action last week when ZEN was in need of a boat driver and an extra set of hands… I qualified. My research focuses on trophic interactions of fishes in seagrass beds—not all that different from the focus of the ZEN projects this summer. What is different is how we think about these systems. I keep reminding the folks in Emmett’s lab that their definition of “predators” is what those of us in the fish world call “prey.” Or what fishermen would call “bait.” It’s all a matter of scale.

And so I found myself in the field with ZEN, and with a few firsts after 4 years of doing field work in Chesapeake Bay. Last week we had one of those early morning tides and correspondingly early start times that made me think staying in and writing statistical code was a good idea. The first morning the alarm went off at 4:30am. My dogs definitely did not want to get up, but they saw the swimsuit and towel as a good sign—they love the beach. Little did they know that today was not their day for a sunrise swim. I made sure I had enough adequate coffee to function, and was out the door. Standing on the boat with the sun rising, I remembered why early field work is so nice: calm water, fresh air, and, most importantly, it’s not so hot! We got to the field site, Pamela got us all organized (which admittedly felt a little like herding cats since several of us were new to the scene), and we set to work installing the cages for an experiment excluding ‘predators’ from patches of Zostera to examine their effects on the seagrass community. I had toyed with conducting a predator exclusion experiment for my own work, but in the end it fell to the wayside—so it was nice to see the set-up and be involved with the execution. We completed the first stage of the set-up before the tide rolled back in and the weather caught up with us.

One of the occupational hazards of field work in southeastern Virginia in the summertime is the random thunderstorm. As grateful as I am to our friends at the National Weather Service for providing quality marine forecasts, even they occasionally get caught with their umbrellas down and we all get soaked. Tuesday was one of those days. We decided to go in the field on the forecast of “morning showers, afternoon thunderstorms,” and again, we had an early start. We motored out to the site, anchored up, had one person in the drink, and then thunder rumbled in the distance. Once, twice and we pulled anchor and ran to our thunderstorm hideout, a picturesque marina at Back Creek on the York River. We tied up just as the skies opened and the thunder boomed overhead. After four years and almost constant, sometimes daily fieldwork in this area, I had yet to duck back into the thunderstorm hideout! Thankfully, there was a nice awning to keep us mostly dry and Pamela had brought some field snacks to keep us happy as we waited for the storm to pass.

After an hour, we were back onsite and installing the second part of the experiment: putting the eelgrass into the cages and populating the cages with grazers. The wind was building and without sun, the water actually was kind of…dare I say…cold! I hopped onto the boat to have a look at the radar (the beauty of smartphone technology!) and things looked clear, so we kept pushing forward, despite the ominous looking clouds over the northeast part of the nearby Mobjack Bay. Sure enough, the next time I checked the radar, 30 minutes later, multiple storms had popped up and things were looking ugly. We called it a wrap, but this time we had no sooner left the site when the skies opened up and pelted us with big, juicy, rain drops. If you’ve never been on an open skiff in pouring rain, you have missed out on the field spa treatment of “dermabrasion”—it feels like you’re being sandblasted! Ouch. While I prefer sunglasses in such conditions to protect my eyes, Serena decided a diving mask was the ticket for protecting her face— she definitely won the field fashion contest! Thankfully, it was just rain with no thunder and lightning, so we pushed on and docked at VIMS looking like a group of drowned sea rats.

By the end of the week we had finished installing the experiment, shored up any caddywampus cages, scrubbed the outside of the cages clean (anyone who owns a boat in these parts can tell you that things in the water get fouled very quickly), and generally made sure the experiment was set. We’ll hope for fewer storms as the experiment continues. While the sun can be hot around here in the summer, it’s much nicer when the wind lays low and the thunderstorms hold off until we’re safe in the lab!

Friendly people, stingrays and turtles: Welcome to Virginia

by Serena Donadi (ZEN exchange student fellow in Virginia)

My ZEN experience for 2012 has begun! Two weeks have already passed since my arrival at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and here is my preliminary evaluation: great people, great place and great work!

First of all, I was impressed by the welcome and friendliness of the people, from my housemates to the VIMS’ stuff. The research group of Dr. Emmett Duffy is composed by graduate and undergraduate students along with apost-doc and technicians working on different projects. What’s really great is the high level of collaboration and interaction within the group. Fieldwork means hard work, limited time (the tides rule our schedule) and often adverse climate conditions (40 degrees Celsius!), and everybody knows that one person can make the difference to successfully reach the goals of the day. Helping each other is also the best way to get to know what other people are working on. Collaboration is the perfect recipe for a highly dynamic scientific environment, and the Marine Biodiversity Lab and others at VIMS are definitely a good example.

What a great place is the Chesapeake Bay! The experimental site of the ZEN experiments this summer is really beautiful. Dense beds of seagrass cover wide areas along the coast and are inhabited by an extremely rich community of organisms. The first day I saw the place I felt a bit like Alice in Wonderland. I put my hands into the dense seagrass bed and I found them covered by tens of giant (at least according to my experience) amphipods, isopods, gastropods… I jumped out of the boat and started walking. Blue crabs (even bigger than my hands!) were hiding everywhere and quickly moved away from my feet. Schools of silversides followed me, maybe attracted by the disturbance and the potential for an easy meal as my feet stirred up the sediment and associated invertebrates as I walked through the seagrass bed.

The women of the ZEN team in Virginia: undergraduates Nicole Rento, Caitlin Fikes and Katelyn Jenkins, graduate student Serena Donadi, and post doc Pamela Reynolds

After collecting myself from the marvel and the surrounding beauty, I helped my team with the tasks of the day: collecting seagrass shoots andepifaunal invertebrates, and catching and measuring mesograzer predators (small fish, crabs and shrimp). With 5 people, we managed to finish before the tide was too high and we jumped on the boat, ready to go back. As a perfect end to my first day of fieldwork, a sting ray swam elegantly in front of us and the head of a terrapin (a type of turtle) appeared at the surface . Maybe they were welcoming me to Virginia, or maybe they were just relieved that we retreating away from their home. I prefer to think it was the former.

Now that I’ve got my feet wet, I’m excited for what other adventures await me here in Virginia!

Meet the ZEN exchange student fellows!

This summer we have four outstanding graduate students traveling to different ZEN partner sites. These ZEN “exchange student fellows” will be assisting with all aspects of the research at their host sites, from fieldwork to labwork, and in the process learning new research skills and about the local culture. See below for a quick synopsis about each of our four student fellows and stay tuned as they will be writing periodic posts about their experiences throughout the summer.

Serena Donadi is a PhD student at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands advised by Drs. Klemens Eriksson and Jeanine Olsen. Serena assisted with the ZEN experiment at the Northern Norway (NN) site last summer. She is working at the ZEN site in Virginia this summer. Her dissertation research examines the role of mudflat ecosystem engineers (cockels, lugworms, mussels) on sediment stability and the structure of the benthic community in the Wadden Sea.

Rachel Gittman is a PhD student at UNC-Chapel Hill working at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, North Carolina, USA, advised by Drs. John Bruno and Pete Peterson. She was the local contact and helped with the ZEN experiments in North Carolina both last and this year. She will be working with Dr. Masakazu Hori at the southern Japan site (JS) and assisting with projects at the northern Japan site (JN) starting at the end of July. For her dissertation, Rachel is studying the effects of shoreline development on functioning in salt marsh and seagrass habitats in coastal North Carolina in addition to exploring food web interactions in these systems.

Nicole Kollars is a master’s student at the College of Charleston in Charleston, South Carolina, USA, advised by Dr. Erik Sotka. She assisted with the ZEN experiment in North Carolina (NC) this summer and will be working with Dr. Massa Nakaoka at the northern Japan (JN) site starting at the end of July. Nicole’s master’s research focuses on the ecological roles of the invasive red seaweed Gracilaria vermiculophylla in the mudflats of the southeastern USA.

Maxwell Overstrom-Coleman is a PhD student at Dartmouth University in Hanover, New Hampshire, USA, advised by Dr. Brad Taylor. He recently started working at the ZEN site in Massachusetts with Dr. James Douglass. Max’s dissertation work focuses on the role of eelgrass as foundation species and their effects on abiotic habitat parameters in estuaries in the northeastern USA.

First Seagrass to see the light (part 2)

by Matt Whalen (VIMS, PhD student at UC Davis)

As I was gearing up for this year’s ZEN experiment in Bodega Bay, CA, I realized that I never finished my story from last year’s experiments in Japan. (Where does all the time go?) Hopefully this belated entry will be a nice way to kick off the 2012 ZEN season.

“Banzai, banzai, banzai!” was one of the first things I heard as my father and I watched the sun rise over the top of Mt. Fuji. It was a long journey—especially if you count my childhood memories of my father’s stories of Japan and his promise that we would one day climb to the top of the iconic mountain—but it was well worth it. There is a saying that goes something like, “You would be a fool not to climb Mt. Fuji, but you would be an even bigger fool to do it twice.” Well, my momma didn’t raise no fool. I really enjoyed that hike and I’m proud to have completed it with my dad, who was only a year out of knee replacement surgery, but the mile-long conga line of hikers ascending just before sunrise made me wish for the relative isolation of many U.S. National Park peaks. This side trip with my dad marked a transition between ZEN experiments and the halfway point in my journey to Japan.

Up north, to the land of Sapporo and snow

The next stage of my ZEN adventure took me to the northern island of Hokkaido, which is far less populous than the ‘main island’ of Honshu and home to the large city and brewery of Sapporo. I was immediately struck at how different this place looked compared to Hiroshima. The architecture was more rustic and functional; the Japanese-style tile roofs of the south gave way to A-frame metallic roofs in Hokkaido with increased seasonality and snow fall in the north. The countryside was also more bucolic in a western sense, with acres of cattle pasture mixed with stretches of corn and soy. It actually bore a striking resemblance to parts of Virginia, where my ZEN adventure began.

My new digs were at the Akkeshi Marine Station just outside of the important fishing town of Akkeshi. Seated at the base of steep cliffs, the laboratory, dormitory, and flagship research vessel were the only manmade structures in sight for a large stretch of the coastline. The coast here bends inward forming the large Akkeshi Bay. On clear mornings, I could easily see the other side of the bay and wisps of inland mountains further in the distance. The bay leads to Akkeshi town, ending in the narrow entrance to an estuary that is nearly as large as the bay itself.

Because it is almost completely enclosed, this estuary is referred to as a lake (Akkeshiko), but it is influenced by the tides throughout its extent and freshwater input comes largely from a single river. The lake is famous for its oysters and, more recently, Manila clams. More importantly for me, it has amazing meadows of seagrass. Nearly the entire estuary is covered with eelgrass whose leaves can grow over two meters in length (that’s over 6 feet!). When boating from one side of the lake to the other, it is necessary to stop and throw the motor in reverse every few hundred meters because the prop gets tangled in seagrass. On the plus side, with each subsequent field trip, we created a channel of sorts from all the lawn mowing and were able to minimize our impacts by following it all the way to our field site.

Unexpected challenges

For this node of the ZEN network, we faced a few challenges. The first challenge was the commute, which either involved a mowing expedition though the eelgrass meadow in a small motorboat or a half-hour drive to the far side of the lake where canoes could be launched in knee deep mud. This later choice was substantially slower but the drive took us through some gorgeous woods where we were ever vigilant for brown bears, which were often seen in those parts (not by any of us, fortunately or unfortunately!). If the potential threat of bears wasn’t enough to hurry us into the water, the clouds of mosquitoes surely helped us shave off a few minutes from the commute. I leave Virginia to fly halfway around the world and still found myself chased by the winged menaces!

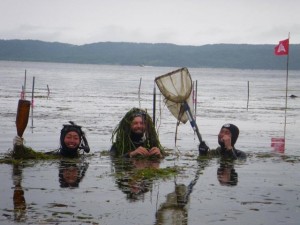

The second challenge was the physical labor involved with field work in such tall eelgrass. Our site was fairly deep, such that at low tide the water came up to just above my waist. With eelgrass well over a meter tall, this made movement between plots as slow as molasses and reduced visibility to the front of our dive masks. I’m used to working in low visibility water in Virginia, but the ribbon-like eelgrass tangling everything was a new beast entirely. We were constantly brushing eelgrass out of our faces while surveying or sampling. And, when we came up for air, we often had wads of grass tugging our snorkels out of our mouths and “Cousin It” inspired eelgrass hairdos. Needless to say, we had to take great care to not rip the eelgrass from the inside of plots or brush off the very epiphytes we were aiming to quantify.

Never judge a jelly by its size

The final challenge made for one of my more memorable and culturally engaging experiences during my time in Japan. It concerned an eelgrass critter that had also visited me on occasion in Hiroshima, a small jelly that densely occupied the ZEN site in Lake Akkeshi. They pack a pretty mild punch (it wouldn’t come close to a box jelly), but when you get stung repeatedly it can take a toll. I experienced some of the pain in Hiroshima, a sharp sting and a long-lasting dull ache, but I wasn’t prepared for Lake Akkeshi.

We were finishing up some work on the weekend, so travel to the field site required both car and canoe. All was going smoothly, my Japanese collaborators and I by this point worked like a well oiled machine. That is, until I unintentionally swallowed some water stuck in my snorkel. Intense stinging in my mouth – that’s what I remember first. I spat and spat, but the stinging did not go away. Next my esophagus was on fire, and then my lower back and most of my joints began to ache. It was a deep ache, down to the bones, that made it hard to move or even think. I had swallowed part of a tiny jelly!

Luckily, I was surrounded by my new friends who loaded me back into the canoe and took me to shore. It took multiple canoe trips to get all the gear and people back to shore so I had to wait on the mudflat in between trips, still in my wetsuit since the mosquitoes were too bad to do anything else. Foundering in the mud with the stinging pain reaching a new peak, I vaguely remember hoping that this was not my day to finally see a brown bear. How I must have looked like an injured seal, covered in dark neoprene and writing in the mud! The decision was made to take me to the hospital, to which I couldn’t object by this time. I was largely incapacitated.

It was quite a while before we made it to the hospital, but I am happy to say that the experience was relatively easy. They had no problem treating me without my passport, and Dr. Hori (the project leader in Hiroshima) stayed with me to translate. To be honest, there was not much treatment that could be offered, although I was given some medicine to ease the pain. I was sent home with a goody bag of prescriptions that I needed more help translating, but I remained restless with pain. It took me another full day to recover completely. On Monday, I returned to the hospital to pay my bill, which was surprisingly modest. Luckily, after a handful of awkward and borderline comical exchanges about worker’s compensation back in the US, I was reimbursed in full. Being a marine ecologist does has its hazards, but I can’t think of anything else I’d rather do.

Jellyfishing in Japan, a short movie made by Matt Whalen based on his encounters with jellies in Japan.

The beauty of it all

All in all, ZEN in Hokkaido was an amazing experience. The eelgrass system there is so full of life. When viewed underwater, the meadow looks more like a forest and, if you are patient and a little lucky, many of the creatures that thrive under the canopy come into view. Small mysid ‘shrimp’ are very abundant here and seem to be important grazers on algae that grow on eelgrass leaves. There are also many abundant species of fish that presumably eat a lot of those mysids and other small grazers. And, of course, there are the jellies. They are actually quite beautiful when you don’t have thousands of nematocysts (their harpoon-like stingers) firing into your tissues!

Mysids on Eelgrass Akkeshi, a short movie by Matt Whalen.

I am so thankful for the opportunity to be a member of the ZEN Japan team during 2011. The country and its people left many lasting impressions on me, and I yearn to go back. Hopefully now that I am based on the West Coast of the USA I will have more opportunities to collaborate with the colleagues and friends I made on my adventure. There are two graduate students traveling to Japan this summer to participate in round two of the Zostera Experimental Network (look for their posts from Japan this summer!) and I hope to live vicariously through them as they travel and conduct experiments. I will be keeping up with their stories from Bodega Bay, CA, where our excellent team has just finished installing a major component of this year’s experiment. I can’t wait to hear about how things go at the other sites and to make more ZEN memories this summer. Dewa mata!