First Seagrass to see the light (part 2)

by Matt Whalen (VIMS, PhD student at UC Davis)

As I was gearing up for this year’s ZEN experiment in Bodega Bay, CA, I realized that I never finished my story from last year’s experiments in Japan. (Where does all the time go?) Hopefully this belated entry will be a nice way to kick off the 2012 ZEN season.

“Banzai, banzai, banzai!” was one of the first things I heard as my father and I watched the sun rise over the top of Mt. Fuji. It was a long journey—especially if you count my childhood memories of my father’s stories of Japan and his promise that we would one day climb to the top of the iconic mountain—but it was well worth it. There is a saying that goes something like, “You would be a fool not to climb Mt. Fuji, but you would be an even bigger fool to do it twice.” Well, my momma didn’t raise no fool. I really enjoyed that hike and I’m proud to have completed it with my dad, who was only a year out of knee replacement surgery, but the mile-long conga line of hikers ascending just before sunrise made me wish for the relative isolation of many U.S. National Park peaks. This side trip with my dad marked a transition between ZEN experiments and the halfway point in my journey to Japan.

Up north, to the land of Sapporo and snow

The next stage of my ZEN adventure took me to the northern island of Hokkaido, which is far less populous than the ‘main island’ of Honshu and home to the large city and brewery of Sapporo. I was immediately struck at how different this place looked compared to Hiroshima. The architecture was more rustic and functional; the Japanese-style tile roofs of the south gave way to A-frame metallic roofs in Hokkaido with increased seasonality and snow fall in the north. The countryside was also more bucolic in a western sense, with acres of cattle pasture mixed with stretches of corn and soy. It actually bore a striking resemblance to parts of Virginia, where my ZEN adventure began.

My new digs were at the Akkeshi Marine Station just outside of the important fishing town of Akkeshi. Seated at the base of steep cliffs, the laboratory, dormitory, and flagship research vessel were the only manmade structures in sight for a large stretch of the coastline. The coast here bends inward forming the large Akkeshi Bay. On clear mornings, I could easily see the other side of the bay and wisps of inland mountains further in the distance. The bay leads to Akkeshi town, ending in the narrow entrance to an estuary that is nearly as large as the bay itself.

Because it is almost completely enclosed, this estuary is referred to as a lake (Akkeshiko), but it is influenced by the tides throughout its extent and freshwater input comes largely from a single river. The lake is famous for its oysters and, more recently, Manila clams. More importantly for me, it has amazing meadows of seagrass. Nearly the entire estuary is covered with eelgrass whose leaves can grow over two meters in length (that’s over 6 feet!). When boating from one side of the lake to the other, it is necessary to stop and throw the motor in reverse every few hundred meters because the prop gets tangled in seagrass. On the plus side, with each subsequent field trip, we created a channel of sorts from all the lawn mowing and were able to minimize our impacts by following it all the way to our field site.

Unexpected challenges

For this node of the ZEN network, we faced a few challenges. The first challenge was the commute, which either involved a mowing expedition though the eelgrass meadow in a small motorboat or a half-hour drive to the far side of the lake where canoes could be launched in knee deep mud. This later choice was substantially slower but the drive took us through some gorgeous woods where we were ever vigilant for brown bears, which were often seen in those parts (not by any of us, fortunately or unfortunately!). If the potential threat of bears wasn’t enough to hurry us into the water, the clouds of mosquitoes surely helped us shave off a few minutes from the commute. I leave Virginia to fly halfway around the world and still found myself chased by the winged menaces!

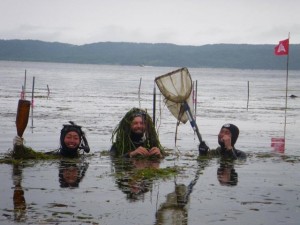

The second challenge was the physical labor involved with field work in such tall eelgrass. Our site was fairly deep, such that at low tide the water came up to just above my waist. With eelgrass well over a meter tall, this made movement between plots as slow as molasses and reduced visibility to the front of our dive masks. I’m used to working in low visibility water in Virginia, but the ribbon-like eelgrass tangling everything was a new beast entirely. We were constantly brushing eelgrass out of our faces while surveying or sampling. And, when we came up for air, we often had wads of grass tugging our snorkels out of our mouths and “Cousin It” inspired eelgrass hairdos. Needless to say, we had to take great care to not rip the eelgrass from the inside of plots or brush off the very epiphytes we were aiming to quantify.

Never judge a jelly by its size

The final challenge made for one of my more memorable and culturally engaging experiences during my time in Japan. It concerned an eelgrass critter that had also visited me on occasion in Hiroshima, a small jelly that densely occupied the ZEN site in Lake Akkeshi. They pack a pretty mild punch (it wouldn’t come close to a box jelly), but when you get stung repeatedly it can take a toll. I experienced some of the pain in Hiroshima, a sharp sting and a long-lasting dull ache, but I wasn’t prepared for Lake Akkeshi.

We were finishing up some work on the weekend, so travel to the field site required both car and canoe. All was going smoothly, my Japanese collaborators and I by this point worked like a well oiled machine. That is, until I unintentionally swallowed some water stuck in my snorkel. Intense stinging in my mouth – that’s what I remember first. I spat and spat, but the stinging did not go away. Next my esophagus was on fire, and then my lower back and most of my joints began to ache. It was a deep ache, down to the bones, that made it hard to move or even think. I had swallowed part of a tiny jelly!

Luckily, I was surrounded by my new friends who loaded me back into the canoe and took me to shore. It took multiple canoe trips to get all the gear and people back to shore so I had to wait on the mudflat in between trips, still in my wetsuit since the mosquitoes were too bad to do anything else. Foundering in the mud with the stinging pain reaching a new peak, I vaguely remember hoping that this was not my day to finally see a brown bear. How I must have looked like an injured seal, covered in dark neoprene and writing in the mud! The decision was made to take me to the hospital, to which I couldn’t object by this time. I was largely incapacitated.

It was quite a while before we made it to the hospital, but I am happy to say that the experience was relatively easy. They had no problem treating me without my passport, and Dr. Hori (the project leader in Hiroshima) stayed with me to translate. To be honest, there was not much treatment that could be offered, although I was given some medicine to ease the pain. I was sent home with a goody bag of prescriptions that I needed more help translating, but I remained restless with pain. It took me another full day to recover completely. On Monday, I returned to the hospital to pay my bill, which was surprisingly modest. Luckily, after a handful of awkward and borderline comical exchanges about worker’s compensation back in the US, I was reimbursed in full. Being a marine ecologist does has its hazards, but I can’t think of anything else I’d rather do.

Jellyfishing in Japan, a short movie made by Matt Whalen based on his encounters with jellies in Japan.

The beauty of it all

All in all, ZEN in Hokkaido was an amazing experience. The eelgrass system there is so full of life. When viewed underwater, the meadow looks more like a forest and, if you are patient and a little lucky, many of the creatures that thrive under the canopy come into view. Small mysid ‘shrimp’ are very abundant here and seem to be important grazers on algae that grow on eelgrass leaves. There are also many abundant species of fish that presumably eat a lot of those mysids and other small grazers. And, of course, there are the jellies. They are actually quite beautiful when you don’t have thousands of nematocysts (their harpoon-like stingers) firing into your tissues!

Mysids on Eelgrass Akkeshi, a short movie by Matt Whalen.

I am so thankful for the opportunity to be a member of the ZEN Japan team during 2011. The country and its people left many lasting impressions on me, and I yearn to go back. Hopefully now that I am based on the West Coast of the USA I will have more opportunities to collaborate with the colleagues and friends I made on my adventure. There are two graduate students traveling to Japan this summer to participate in round two of the Zostera Experimental Network (look for their posts from Japan this summer!) and I hope to live vicariously through them as they travel and conduct experiments. I will be keeping up with their stories from Bodega Bay, CA, where our excellent team has just finished installing a major component of this year’s experiment. I can’t wait to hear about how things go at the other sites and to make more ZEN memories this summer. Dewa mata!

Road trip to North Carolina

by Paul Richardson (VIMS technician)

photos by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN coordinator)

The road trip begins!

On Friday, June 1, 2012 undergraduate student Katelyn Jenkins and I loaded up a fancy Ford F-150 rental truck with filters, jars, vacuum pumps, and neoprene and set out for The University of North Carolina’s at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences (UNC-IMS) in Morehead City, North Carolina to help Erik Sotka’s (College of Charleston) group break down this summer’s main ZEN experiment. It was a marathon of work, but the good company, nice scenery, rocking tunes, and Oreo cookie snacks made the time fly. We amassed a large group for the effort. Erik’s graduate students, Nicole Kollars and Courtney Gerstenmeier, and his REU intern, Aaron joined Katelyn and me along with UNC-IMS local, Alyssa Popowich to comprise a formidable experimental breakdown team.

Katelyn and I arrived a bit earlier on Friday than the South Carolina contingent, so we helped Alyssa prepare tin envelopes that are used for drying samples in the lab. This prep work was a key task and streamlined the next two days. After helping Alyssa, we grabbed a quick dinner in town and then met up with Erik’s crew. As with any major experimental endeavor, a trip to the store was necessary for last minute supplies which this time included hundreds of Ziploc bags for collecting and storing field samples.

Rocking out in the field and the lab

This was our first major ZEN experiment event in North Carolina without the presence of Pamela Reynolds, the ZEN coordinator, which made us all a bit nervous, but her and Erik’s extensive planning paid off and this was an extremely efficient and productive experimental breakdown. I really enjoyed working with Erik and his crew. Everyone was so positive and they all had an unyielding work ethic. I also learned something interesting about Erik when I asked about the band that he played in back when he was in graduate school. Pamela tipped me off to this fact but she was vague on the details. When I asked Erik, he said it was his only “brush with fame” when he played with the band Cake before they were big. Wow, what a huge ‘brush’! I love Cake. As you may know, Cake is a talented rock band from Sacramento, California with a keystone trumpeter, Vince DiFiori. As Erik said, “Cake would not be Cake without the trumpet,” and I agree! But, during Cake’s embryonic stage they experimented with other wind instruments which included Erik on the saxophone. In another universe, Erik is a music rock star. In this universe, he has to settle with being a marine ecology rock star. Tough break.

Luckily Aaron brought his iPod loaded with thousands of great songs, which kept things lively in the lab as we processed samples. I know it sounds like I’m getting off track here, but good music is essential for tedious long stretches of labwork!

Never a boring moment

One thing that we didn’t do was go sightseeing. Before we left Pamela told me that I should check out some of the various parks andbeaches, (including Fort Macon) if I had the time. While we didn’t have any extra time for sightseeing (I’ll save that for a family vacation) I did see plenty of pretty sights during the course of our field work. Carrot Island on the right and the town of Beaufort on our left made for nice scenery as we motored out to the field site in a local Carolina skiff. A short boat ride towards the inlet brought us to the field site in the Rachel Carson Reserve, which is adjacent to a gorgeous system of Spartina marsh islands called Middle Marsh.

Comparing Virginia and North Carolina

At first glance, the marine environment of Bogue Sound appears similar to the Chesapeake Bay but a critical eye will notice some striking differences. The most conspicuous difference that I noticed was the abundance of intertidal oyster reefs. We had to traverse one to get to our seagrass bed. We used to have numerous oyster reefs in the Chesapeake, but overfishing and disease have had their toll and they have yet to recover. Another interesting comparison was the abundance of sea urchins and brittle stars at Middle Marsh. These animals are rarely, if at all, found in the York River and western side of the Chesapeake Bay, but were all over the place at Middle Marsh. I even saw an urchin hanging out in the middle of one of our experimental plots!

Tiny drifters make fieldwork challenging

Eelgrass at the ZEN field site in Middle Marsh, North Carolina is home to many marine invertebrates, some benign and others best left undisturbed

Another less exciting difference between the VA and NC ZEN sites was the abundance of hydroids (small jellies). As soon as I waded into the knee deep water and began admiring the lush bed of the eelgrass Zostera marina, a stinging sensation spread along my legs. By the end of the day we were all envious of Nicole, who was smart enough to wear knee high neoprene boots. Although it wasn’t as sharp as a bee sting or even your standard sea nettle, the thoroughness of stung surface area did give the mild sensation that the flesh was melting off of my legs. This was especially true when I showered with fresh water that first night and any remaining unengaged nematocysts (the specialized cells jellies sting you with) exploded into my skin. I’m just glad the water was only knee deep! Alyssa and Pamela warned me about this, but it was too hot to wear a wetsuit and I didn’t have an appropriate dive skin. But, I wasn’t the only one, so there was plenty of camaraderie. The stinging took a few days to go away – a not so pleasant reminder of an otherwise enjoyable experimental breakdown!

Wrapping up

Sunday was another marathon, but this time in the lab. We processed seagrass shoots and scraped off the epibionts (animals and plants living on them), and sorted and preserved the associated mesograzers along with other field samples. We split into two teams to divide and conquer! Except for a short lunch break, we went full tilt until, suddenly, it was 7pm. With the fieldwork completed, lab samples processed, and the local lab somewhat straightened up, we packed up our gear and hit the road. What we planned to take us four days we completed in two. We made it back to Virginia a little before midnight and I slept like a rock. The sun, salt and intense fun of fieldwork will always be my preferred sleeping pill!

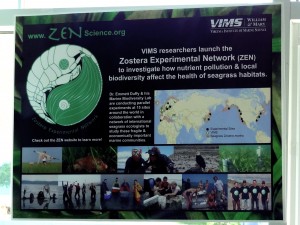

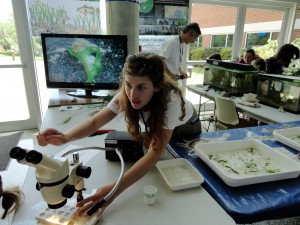

ZEN at Marine Science Day 2012

by Pamela Reynolds (ZEN coordinator)

We introduced the Zostera Experimental Network to the public of Virginia at the tenth annual Marine Science Day (MSD) event at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) in May, 2012. Over 2,000 people visited the VIMS campus in Gloucester Point, VA for a full day of behind-the-scenes learning about marine science and the Chesapeake Bay.

Our Marine Biodiversity Lab ran an touch tank exhibit titled “Secretive Seagrass Creatures” where kids and adults had up close encounters with mesograzers and the fish, crabs and shrimp that live in local seagrass habitats. We even hooked up a high definition video camera to one of our microscopes so everyone could watch an amphipod graze on algae and make a mucus tube.

The public was very receptive and inquisitive, especially regarding the ZEN.

Questions we were frequently asked:

Q. What do you mean everyone at the different ZEN field sites did the same experiment?

A. We shipped boxes of experimental materials and sent copies of a detailed protocol (a “how to” guide book), along with instructional videos, to all of the other scientists to ensure that everyone used the same methods. The videos were great as not all of the participating students from the other countries spoke fluent English.

Q. How can you compare the Chesapeake to somewhere like Norway or Alaska? Isn’t it colder up there?

A. Yes, it most definitely is! And this variability, or differences in environmental conditions such as temperature and salinity, is very important. By having a range of environmental conditions, we have more power to understand how these factors such as being in a colder or warmer place can affect the important seagrass communities we are studying.

Q. How do you know these mesograzers are important? They’re really small. Don’t turtles, herbivorous fish and other larger marine animals eat more?

A. Although mesograzers such as amphipods are small, they can eat a lot of algae, especially the algae that grows on the leaves of seagrass and competes with the seagrass for light and nutrients. We have conducted many experiments in tanks and have found that mesograzers can do a good job at keeping the seagrass clean and promoting its growth. While turtles and fish may have larger mouths and take bigger bites of algae, they aren’t necessarily eating the same types of algae or the algae growing on the seagrass, and these larger herbivores aren’t found all over the world. Mesograzers, however, are everywhere and can be very abundant. If you grab a big handful of seagrass in the Chesapeake you can catch hundreds of amphipods!

Q. I live near the Chesapeake. Why should I care about seagrass in Japan or Sweden?

A. By studying other places we can understand how regional and global issues such as pollution, overfishing and seawater warming can threaten our local systems. Oceans make up about 70% of the Earth, and most of them are connected. If we only study the Chesapeake, we loose a valuable opportunity to help understand and predict future challenges.

Our one shortcoming from this year’s Marine Science Day – no one dressed up like an amphipod or other mesograzer for the annual Parade of Marine Life, although while cleaning up our lab we did find a child-sized Idotea (a type of marine isopod) costume from years past. Next time!

ZEN at the 2012 Benthic Ecology Meeting

The Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN) team formally emerged into public view for the first time at the Benthic Ecology Meeting this past week in Norfolk, Virginia. ZEN coordinator Dr. Pamela Reynolds (top center in the photo, in red) presented a first look at the results of our 2011 experiment evaluating the relative importance of grazing, nutrient loading, and abiotic forcing on dynamics of eelgrass (Zostera marina) communities across the Northern Hemisphere.

ZEN had representation from several of our 15 global sites, and a diverse group of PIs, grad students and undergrads, at BEM this year. These included teams from northern Japan (PI Massa Nakaoka and grad student Kyosuke Momota), Quebec (graduate students Julie Lemieux and Laetitia Joseph), Massachusetts (PI James Douglass), North Carolina (PI Erik Sotka, grad students Rachel Gittman and Nicole Kollars, technicians Danielle Abbey and Alyssa Popowich), and Virginia (Emmett Duffy, Pamela Reynolds, Paul Richardson).

The abstract of Pamela’s presentation:

A comparative-experimental approach reveals complex forcing among bottom-up and top-down processes in seagrass communities across the Northern Hemisphere

Pamela L. Reynolds (1); Emmett Duffy (1); Christoffer Boström (2); James Coyer (3); Mathieu Cusson (4); James Douglass (5); Johan Eklöf (6); Aschwin Engelen (7); Klemens Eriksson (3); Stein Fredriksen (8); Lars Gamfeldt (6); Masakazu Hori (9); Kevin Hovel (10); Katrin Iken (11); Per-Olav Moksnes (6); Masahiro Nakaoka (12); Mary O’Connor (13); Jeanine Olsen (3); Paul Richardson (1); Jennifer Ruesink (14); Erik Sotka (15); Jay Stachowicz (16); Jonas Thormar (8)

(1) Virginia Institute of Marine Science, (2) Åbo Akademi University, (3) University of Gronigen, (4) Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, (5) Northeastern University, (6) University of Gothenburg, (7) Universidade do Algarve, (8) University of Oslo, (9) Fisheries Research Agency, Japan, (10) San Diego State University, (11) University of Alaska Fairbanks, (12) Hokkaido University, (13) University of British Columbia, (14) University of Washington, (15) College of Charleston, (16) University of California Davis

Two fundamental challenges to prediction in ecology are complexity and idiosyncrasy. How do we evaluate the importance and generality of multiple, interacting factors in mediating ecological structure and processes? One promising way forward is the comparative-experimental approach, integrating standardized experiments with observational data. In summer 2011 the Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN), a collaboration among ecologists across 15 Northern Hemisphere sites, initiated parallel field experiments exploring bottom-up and top-down control in eelgrass (Zostera marina) communities. Eelgrass is among the most widespread marine plants, forming ecologically and economically important but threatened coastal habitats. We factorially added nutrients and excluded small crustaceans (mesograzers) using a degradable chemical deterrent for four weeks, and measured responses of associated plant and animal communities. As expected, results varied strongly across the global range. Our cage-free deterrent strongly reduced crustacean grazers; at several sites grazer exclusion released blooms of epiphytic algae and/or sessile invertebrates. In Chesapeake Bay, these blooms reduced eelgrass biomass after eight weeks, demonstrating mutualistic dependence between eelgrass and mesograzers. Surprisingly, nutrient addition had little effect on epiphytes, except in Massachusetts and Sweden where grazers are suppressed by mesopredators. Ongoing research is analyzing the relative influence of grazer diversity and environmental forcing in mediating these processes.

Analysis of the 2011 experiments is still under way–even as we swing into high gear for planning the 2012 experiment. We will be presenting the complete results of the 2011 experiment at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland (August 2012) and the 47th European Marine Biology Symposium in Arendal, Norway (September 2012). We hope to see you at one or another of these events!

Typical day at the ZEN British Columbia field site

by Carolyn Prentice (Univ. British Columbia undergraduate at ZEN Vancouver, British Columbia Site)

My experience working on the ZEN project in Dr. Mary O’Connor’s lab this past summer was simply fantastic. It was great to have a summer job that I was really passionate about; anytime anyone asked me what I was doing for the summer, they were in for more than just a one-sentence answer! It was also great to share the experience with many other passionate biologists; we had an amazing group of workers and volunteers. Even when it was rainy and windy and our hands were numb, we knew we were lucky to be doing what we were doing! I am grateful to have had such an amazing opportunity, especially as an undergraduate and working on the ZEN project has certainly inspired me to continue studying the fascinating communities that inhabit Zostera marina beds. I am also excited to see the results of the ZEN projects from all of the different sites!

A typical day for the crew at the ZEN B.C. site:

1. Pile into the U.B.C. Zoology van with equipment and keen volunteers.

2. Arrive at the field site, put on (leaky) chest waders and sun hats or rain jackets (typically the latter).

3. Head down the 300 or so stairs to the beach, pass all of the locals getting their daily exercise and wearing ‘what are you guys up to’ looks on their faces.

4. Head out onto the mud flats, try not to stop moving or risk getting stuck in the really sticky mud.

5. Go about whatever task we had set out to do that day. Meanwhile, enjoy the beautiful scenery – the nearby Gulf Islands, the B.C. Ferries sailing across the Straight of Georgia, and hundreds of foraging herons.

6. Walk back up the 300 or so stairs (great exercise!)

7. Empty the leaky waders.

8. Go to Tim Horton’s to get iced caps or hot chocolates (typically the latter) before heading back to U.B.C.

9. Go home feeling like the luckiest people in the world!

A Marine Ecologist’s New Year’s Resolutions

by Pamela Reynolds

1. Finish and submit those pesky, lingering manuscripts.

2. Apply for more funding.

3. Make more time for broad reading of the literature.

4. Figure out the species identification for sample “unknown A”… and “B”… and “C”…

5. Go digital and print less.

6. Appreciate the learning experience that comes with syntax errors in my statistical analysis coding.

7. Get out into the field more.

8. Spend less time fiddling with powerpoint slide aesthetics.

9. Fix that tear and other leaks in my wetsuit.

10. Bring healthy snacks into the field.

11. Cleanup my e-mail inbox.

First grass to see the light: ZEN in Japan

by Matt Whalen (VIMS, UC Davis graduate student)

I was excited to participate in the ZEN project because of the preliminary work I did for my Master’s research under Dr. Emmett Duffy at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) to test the methods in seagrass. I was also excited for the chance to get up close and personal with eelgrass (Zostera marina) in different parts of the world. I had visited eelgrass beds in Boston, Massachusetts, Bodega Bay, California, and Vancouver, Canada while visiting grad schools, and played around in tropical seagrasses in Florida while helping out with a seahorse research project a few years ago, but the bulk of my research experience in seagrass was focused on the lower Chesapeake Bay. When I found out that I would be traveling to Japan to work on not one but two of the ZEN experiments, I felt like a boyhood dream had come true. Sappy, but it’s 100% accurate. My father lived in Japan for a number of years while he was in the navy, and growing up I heard a lot of stories about his time there that romanticized the whole thing for me. He even promised me (around the time I started tying my own shoes) that we would travel to Japan together one day to climb Mt. Fuji.

The timing of the trip could not have been more perfect. At the conclusion of my Master’s degree at VIMS and before beginning my PhD at UC Davis. I spent a month and a half in the land of the rising sun. My time was split between Hiroshima Prefecture, Tokyo and surrounding areas, and the northern island of Hokkaido. No amount of Japanese anime (my favorite series being Cowboy Bebop and my most recently viewed film a Japanese rendition of the Little Mermaid named Ponyo) could have prepared me for how amazing this trip would be. My first impressions were actually in the airport and during the flight. I had scored direct flights from Washington, D.C. to Tokyo and I flew with ANA (All Nippon Airways)…“Nippon” and “Nihon” are Japanese (Nihongo) for Japan, and I’m not sure how “Japan” came into use. As is often the case (for me, anyway), international flights are far superior to domestic US flights, and ANA exceeded anything I had experienced before (I’ll let the better-traveled out there decide whether ANA or international flights generally are superior).

I made a quick list of why these international flights were awesome: Continue Reading

Thanksgiving

By Pamela Reynolds, ZEN Coordinator

I am thankful for:

1. Enthusiastic undergraduate students

2. Patient collaborators

3. Sunny field days

4. 7 mm wetsuits without holes

5. Watermelon slices and Oreos in the field

6. Days without R-syntax errors

7. Extra cable ties

8. Shipments that arrive on time

9. Polarized sunglasses and wide brimmed hats

10. Understanding partners and family

Science – it’s electric!

By Pamela Reynolds (VIMS; ZEN Coordinator) with contributions from Paul Richardson and Akela Kuwahara

There are few times in my life that I can honestly say that I was terrified. Feeling the Loma Prieta earthquake in ’89, (nearly) tripping over a cottonmouth snake, taking my qualifying exams all stand out. So does the 28th of June in 2011.

It started out as a normal day, or at least as normal as a day of fieldwork can go at the ZEN site in Virginia. It began with the usual flurry of activity in the early morning packing the experimental equipment and loading the boat, checking the associated weather websites and filling out the float plan, slathering on sunscreen and pulling on life jackets and dive booties. It was a typical hot, humid, and sunny summer field day in coastal Virginia.

As is customary, when we arrived at the site Captain Paul cranked up the VHF radio to the weather channel and its droning computerized voice began babbling in the background. We set anchor, grabbed our masks and associated collecting gear, hopped into the water, and got to work. We were collecting seagrass shoots to measure growth rates, which involved a lot of swimming and diving among our experimental plots in what we affectionately called the ZEN Pole Garden. On about plot number 22, half way through our collections shortly after 3 o’clock in the afternoon, it started. That dreaded cacophony over the VHF radio followed by the ominous blaring of the weather alarm and the warning statement that can mean only one thing – storm!

I never used to be afraid of lightning. I actually found it to be beautiful, exciting even; an awesome display of the raw power of nature ripping the sky above. My sentiments have changed. Continue Reading

A summer of adventure

By Akela Kuwahara, VIMS REU student summer 2011 (Humboldt State University)

Last week I earned my Invertebrate Zoology team at Humboldt State University 10 extra credit points for successfully identifying a gammaridean and caprellid amphipod, a mysid shrimp, and several Palmonetesshrimps! How, you ask? One word: ZEN.

This past summer I was in the REU program at VIMS working with Dr. Duffy’s Marine Biodiversity Lab. The ZEN project had just begun when I arrived in Virginia and I quickly set to work making experimental equipment and processing seagrass samples. Coastal Virginia looks nothing like the rocky California Coast where I currently go to school at Humboldt State University, nor like where I grew up on the Big Island of Hawaii.

I have had few experiences as enriching, educational, and career-focusing as my internship with the VIMS ZEN team. I had an up-close encounter with a juvenile terrapin who tried to nest in my hair, and an encounter with a sea nettle that wrapped my leg in a less than tender embrace. I became an expert at pouring cups of wet plaster, identifying a severed head or lone backside of the tiny amphipod Gammarus mucronatus, distinguishing between seagrasses Ruppia and Zostera, doing the sting-ray-shuffle, writing international UPS labels in the nick of time, and so much more.

Sadly, since my time at VIMS has ended, these skills have been poorly utilized. They have, however, given me a better understanding of marine ecology and the functioning of seagrass habitats, and they’ve earned me 10 extra credit points in Invertebrate Zoology! Emmett Duffy’s lab at VIMS is a craftily chosen group of people who have collectively helped to steer my interest in graduate studies towards subtidal ecosystems and their global presence and impact. I can’t wait to hear about where the ZEN is headed, and the progress that it has made. It was a summer well spent.

Photos by JE Duffy, PL Reynolds, JP Richardson